How and what to heritagise in a region “devoid” of heritage? A walking seminar through Veneto

In mid-September, I took part in the first walking seminar as a new member of the Heritage on the Margins programme group, which on this occasion took place at the westernmost edge of the Slovenian presence in present day Italy: in Venetian Slovenia. The aim of the two-day walk was to give the group members the best possible insight into the heritage and heritage management of the area by focusing on a comparison of two micro-areas (the eastern part on Day 1 and westernmost part on Day 2) that were impacted differently in the recent past, due to the difference in strength of the 1976 earthquake, a disaster that destroyed a larger part of building stock in the western part than in the east.

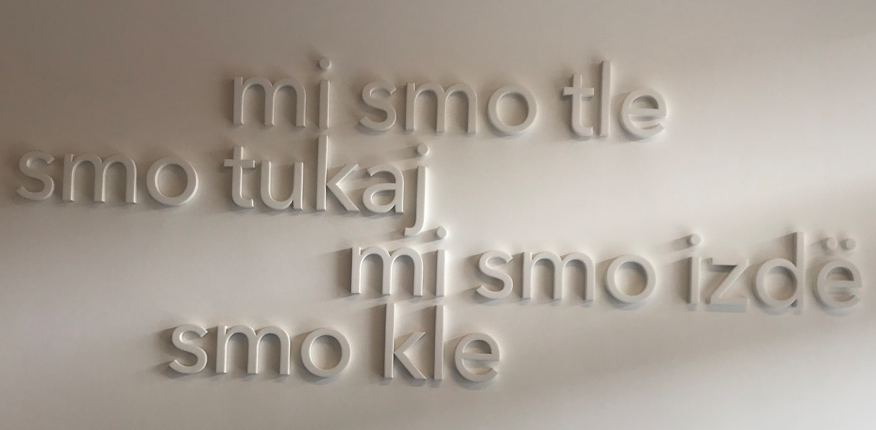

On the first day, Monday 11th September 2022, we departed Ljubljana in the early hours of the morning and arrived in front of the SMO (Slovensko multimedialno okno – Slovenian Multimedia Window) Museum in Špeter (it. San Pietro al Natisone), which lies at the centre of the Natisone valley, stretching between the easternmost edge of Friuli and the upper reaches of the Soča and Gorizia. The museum presents the cultural landscape from Mangart in the Julian Alps to the Gulf of Trieste. At the entrance to the museum, the wall is decorated with the inscription MI SMO TU (WE ARE HERE), a reminder that Slovenians also live in Italy (this was also the title of a concert held in November 2012 celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Pinko Tomažič Partisan Choir in Trieste).

The museum’s modern design and layout place it alongside thematic and provincial museums that are no longer based on the collection of objects, but on the narrative and occasional artistic-experimental representation of the heritage of these areas. It is a “growing” museum, as, in addition to documenting, it also provides a constantly evolving archive and addition of new content. The museum offers visitors interactive journeys through multimedia presentations that no longer require a guided tour of the museum, but encourage them to visit on their own, with several hours of recordings that invite them to lose themselves in the times of the picturesque landscapes of Trieste, Gorizia and Udine. We viewed the formation and transmission of heritage in a modern way: through a video-story and an interactive map that changed as we watched following a timeline. The new age digitised collection in Špeter is a kind of counterpoint to the ZBORZBIRK project, where the purpose of this project is to professionally treat, evaluate and promote cultural heritage collections created by local people. These collections are distinct cultural treasures of the Valcanale Valley, the Resia region, the Natisone River Valley, the Torre Valley on the Italian side of the border, and of the Upper Sava Valley, the Tolmin region, Kambreško, Lig and the Brda hills on the Slovenian side.

In Masseris, we were welcomed by the energetic Luisa Battistig, an expert in local customs, culture and language, guardian of the Matajur Museum and President of the Venetian Mountaineering Family. In contrast to the SMO, its collection of old objects is a classic ethnological collection or ethnological museum, through which Luisa guided us by narrating in dialect. The Smithy, a collection of preserved blacksmith tools, looked as if no one had set foot in it for a century, with all the necessary pieces and tools.

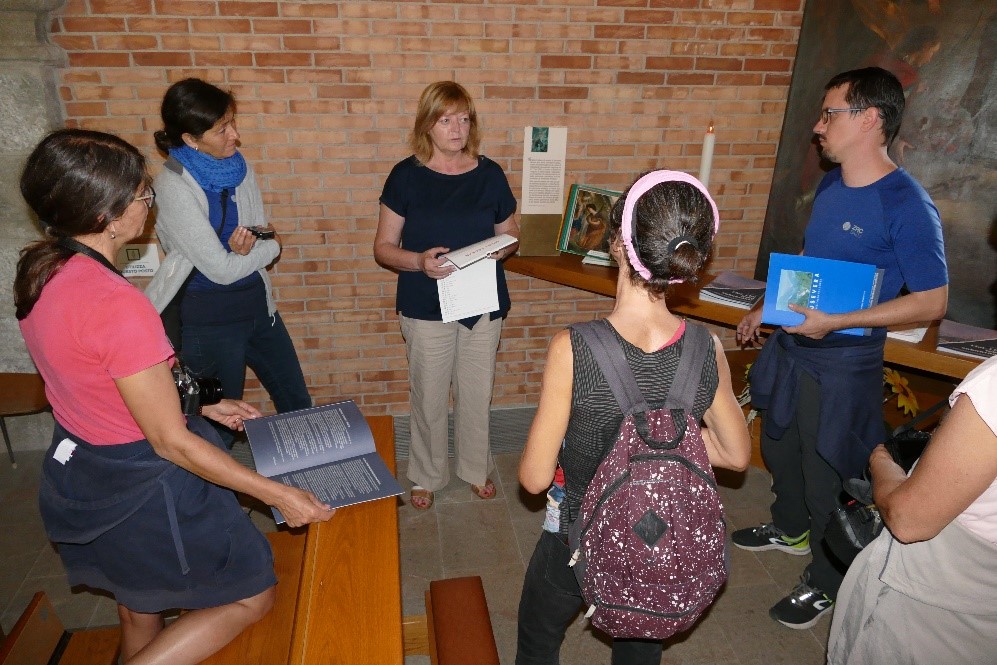

In the village of Matajur (it. Montemaggiore) we met parish priest, Božo Zuanella, who gave us a presentation of the linguistic situation of the area over time in the local church; in contrast to Mrs Battistig’s dialect, the priest spoke or lectured in educated and/or colloquial Slovenian, as he had at least partly attended school and lectures at the University of Ljubljana in educated Slovenian.

This was followed by a late afternoon hike to Matajur, the “sacred mountain of the Venetian Slovenians”, the symbol of the area, with even the local weekly newspaper of the Slovenians of the Udine region, Novi Matajur, being named after it. The image of this border hill is also deeply rooted in the folk tales of these places, such as the tale of How the Giants Helped the Little Girl (Kako so velikani pomagali Čečici). We made a stop at the Venetian Mountain Family hut, which is located at 1545m.

The mystique of Matajur touched us all and we forgot about the time; so, we set off by car after dusk through Breginj, Tipana (it: Taipana) and Viškorše (it: Monteaperta), arriving by nightfall at Bardo (it: Lusevera) in the Tersko (it: Torre) valley. An excellent dinner awaited us there, seasoned by hunger. Igor Cerno from Bardo, a speaker of the Tersko dialect, also a member of the BK evolution musical group (BK stands for Venetian Roots), joined us for dinner and gave us his experience and the current linguistic, cultural and political situation of the area. After dinner, we had an evaluation workshop late into the evening and went to bed well after midnight.

On the second day of the hike, together with local cultural worker, Mrs Luisa Cher, who began by telling us a story in the Tersko dialect, we then visited the Church of St George, where she read us another story from their almanac also in dialect, and then onto the museum collection in Bardo Ethnographic Museum.

After this intense morning of absorbing heritage in Bardo, we headed to the village of Breg (it: Pers) and crossed the Bedroža Valley (it: Vedronza) on foot to Fejplano (it: Flaipano) – both places represent the westernmost historical points of the Slovenian linguistic area and are also the closest to the epicentre of the earthquake. The walk was through difficult terrain, on steep slopes and narrow winding paths, such that we hikers could better imagine how people got around, went to work, went to church, visited relatives from the neighbouring village…. In the afternoon we headed to Čedad (it: Cividale del Friuli), where we had a final evaluation in a central square café, and then continued our journey back to Ljubljana.

.

So, what are the characteristics of heritage in this area? Summarising our impressions at home, we could see that although there are some differences between the western and eastern parts of Veneto, the two areas are quite similar in terms of historical, social and economic development: even though today, both face similar contemporary challenges, above all depopulation. The two areas were affected in fundamentally different ways by the devastating earthquakes of 1976. In the eastern part, the infrastructure remained relatively well preserved, while the western part, which is only about 10 km as the crow flies from the epicentre of the earthquake, was flattened. The latter has a different attitude towards heritage: it was not about restoring or reviving, but rather about recreating heritage, such that the people here do not have such a nostalgic attitude towards heritage, but are actually oriented towards the needs of the future (rather than bemoaning the past) when it comes to heritage; they see new buildings and the introduction of innovations as an opportunity for a symbiosis of the old and the new, a kind of bridge between the past and the present. As for the future, they have a rather realistic but not necessarily negative view. The observer gets the feeling that heritage processes in the west are not so much rooted in anxiety about what future generations will do with it, as is evident in the east: even if their dialect dies out one day, their culture and architecture will remain – even if modernised.

Let me conclude with the song “Štupienjo za štupienjo ” (“Step by Step”), whose lyrics and music (in dialect: “besiede an glasbo”) were written by Venetian singer-songwriter – the late Francesco Bergnach – Kekko. The song is about the love of one’s home, which is left behind as one needs to go elsewhere to earn money, far away from their dwelling and home.

Štupienjo za štupienjo, / gor po dugi (Sln. dolgi = An. ‘long’) pot,

ostane zad za mano moja hiša.

Štupienjo za štupienjo, / oku (Sln. okoli = An. ‘around’) mene pogledam,

in videm mojo zemjo, / se zgubja mimo.

Drevje, se mi zdi, / lietajo prout mene,

potle jih videm majhane, / se zgubjajo.

O zemja, o vas, o bratri (Sln. bratje = An. ‘brothers’), / pustim vas an lohni,

vič vas ne bom videu, / muoram iti za ušafat (Sln. ustvariti = An. ‘to create’),

ki malega vič.

Štupienjo za štupienjo, / napri (Sln. naprej = An. ‘forward’) hodim še,

sonce vesoko sieje, / se zdi pozdravjat.

Perja sada šumjo, / bi tiele rade reč,

pridi preca, parjateu (Sln. prijatelj = An. ‘friend’), / tle med nas.

Se uarnem (Sln. vrnem = An. ‘to be back’), lepa vas, / se uarnem, hribi zeleni,

bom poslušu še šum / od vode, ki se stieka,med travo an robieh / od moje vasi.

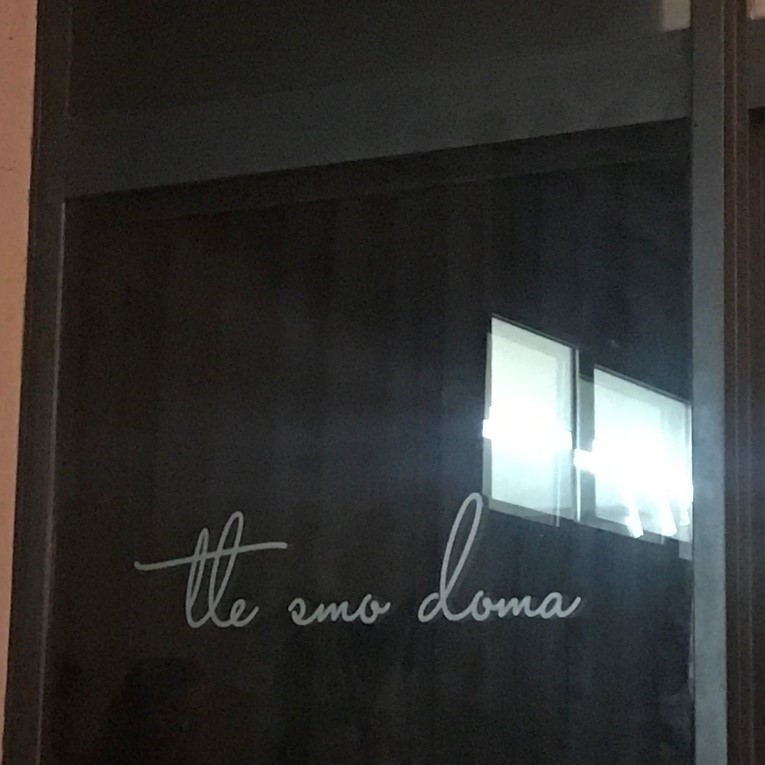

PS: On my return to Ljubljana, I stopped at a concert in Ljubljana’s Prulček (a performance by the children of the walking seminar participants), where I came across a sign that reminded me of the very start of our walk (cf. Fig. 1):