Sečovlje salt pans: heritagisation of culture or nature?

Introduction

The landscape of the Sečovlje salt pans was studied through literature, films, videos, volunteer work and in-depth visits. This paper highlights the uncoordinated activity between the actors or managers of (new) nature and culture and encourage their integration. In the case of the Sečovlje salt pans, there are two main actors: the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park (the concessionaire for the period 2001-2021 is the company Soline, a salt production company (Soline, pridelava soli, d.o.o.) owned by the Slovenian telecommunications company Telekom Slovenije) and the Museum of Salt Making, which is part of the Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum Piran.

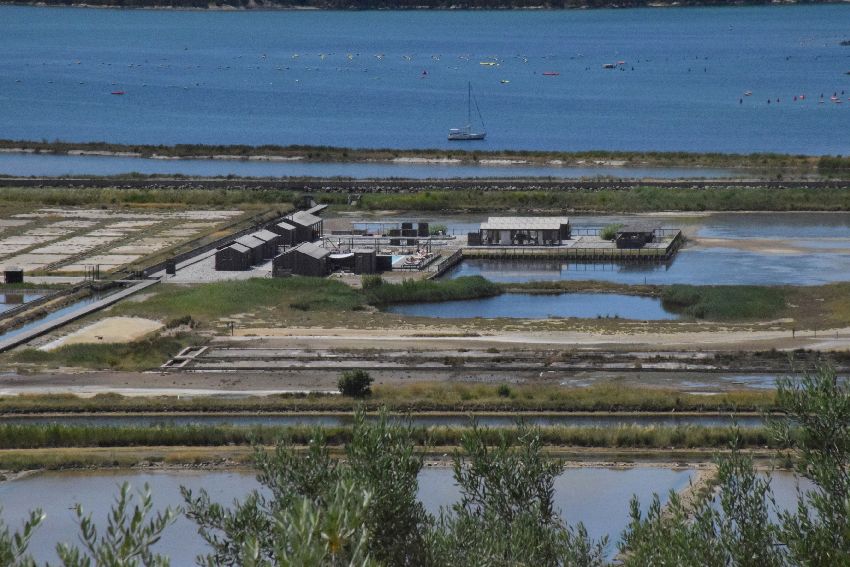

Sečovlje salt pans and salt farming

The Sečovlje salt pans are a cultural landscape in the Bay of Piran in Slovenian Istria, bordered to the north by the flysch Koper Hills and to the south by the Buje Karst in Croatia.

Apart from the Strunjan salt pans, the Sečovlje salt pans, with an area of 593 hectares, are the only ones among the former salt pans of Piran that have been preserved and insist on the traditional method of salt extraction. Their development probably began in ancient times, with the first written records dating back to the 13th century (Pahor and Poberaj 1963). For centuries, the economic development of Piran was based on the extraction and trade of salt. During the Venetian Republic (9th-18th centuries), up to one third of all sea salt on the eastern Adriatic coast was produced by the Piran salt pans (Savnik 1951; Savnik 1965; Bonin 2016).

The salt workers continuously adapted to the natural conditions and improved their knowledge and skills. In 1377 they took over from the Dalmatian salt workers the production of petola, a biosediment made of minerals and microorganisms, which allows the production of extremely pure salt. The whiteness and quality of Piran salt made it highly sought after.

The salt workers renewed the salt fields and equipment in winter and harvested the salt in summer ([[Žagar 1992a]g). During the salt season, the inhabitants of Piran, about 400 families or 3800 to 4200 people, migrated to temporary dwellings in the salt pans 10 km away.

The northern part of the salt pans, Lera, and the southern part, Fontanigge, differ considerably. They are separated by the Drnica River, also known as the Canal Grande or the old Dragonja riverbed. In 1912, during the Austro-Hungarian period, the medieval method of salt extraction was abandoned in Lera and the extraction process was modernised. The typical industrial division of labour was introduced and the wind pumps were replaced by diesel and later by electric pumps. The constant presence of salt workers was no longer necessary, but manual salt extraction has been maintained until today. After the Second World War, most of the sea salt pans on the northern Mediterranean coast were closed down due to lack of competitiveness. In the Fontanigge area, the medieval structure of the salt pans and the working methods have been preserved for 55 years longer than in Lera. Due to political and socio-economic changes, including the industrialisation and urbanisation of Slovenian coastal towns, they were finally abandoned in 1967 (Savnik 1965; Topole and Pipan 2022). The period of heritagisation of the salt pans had begun.

“Musealisation”of medieval salt farming

After the abandonment of the salt pans (Pahor 1972a; Pahor 1972b), Miroslav Pahor, the director of the Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum Piran, made efforts to open a museum of salt making and to enhance the value of tourist experience in the area. In 1984 and 1985, in agreement with the Intermunicipal Institute for the Protection of Natural and Cultural Heritage Piran and the salt workers, its location was determined along the Giassi Canal in the Fontanigge area of the Sečovlje salt pans. In 1990, the Municipality of Piran declared the area of the Sečovlje salt pans the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park (Odlok 1990) and established protection regimes and development guidelines. A year later, the Museum of Salt Making was opened in the restored salt-pan house as part of the Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum Piran (Benčič Mohar 1992; Ravnik 1992; Žagar 1992b). The designated landscape area and the Museum of Salt Making were granted state protection status in 2021 (Odlok 2001; Uredba 2001).

The museum later expanded its collection and established a learning centre. With the aim of preserving salt-making facilities and skills and promoting salt extraction, it organised international summer work camps for volunteers from 1999 to 2014 and was awarded the EUROPA NOSTRA medal in 2003 “for exemplary and sensitive revitalisation of the cultural landscape, including the restoration of facilities for traditional salt production technology, architectural restoration and educational activities, all in close harmony with the natural environment” (Topole and Pipan 2022).

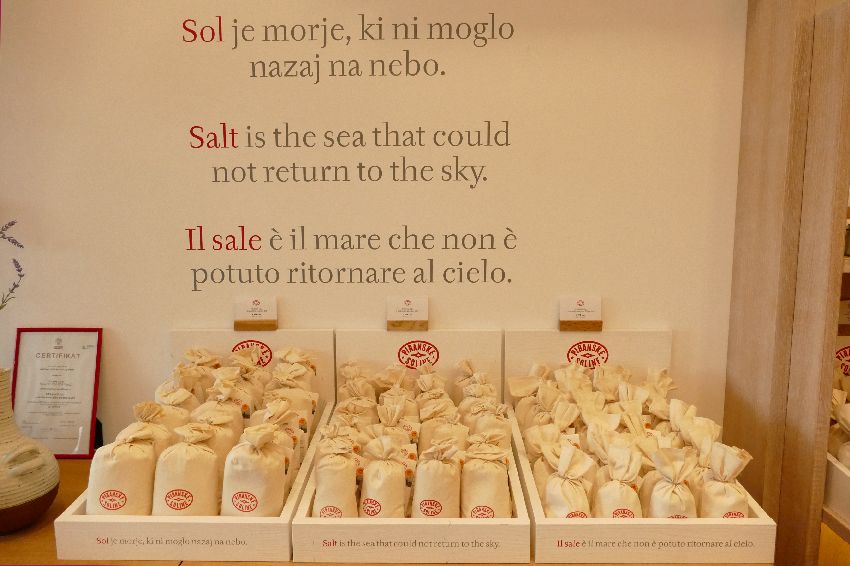

The Sečovlje salt pans trademark, protected designation of geographical origin and intangible cultural heritage

The company Telekom Slovenije has become aware of the tourist potential of the Sečovlje salt pans and at the same time of the exceptional mineral wealth of the Sečovlje salt. In 1999, it took over the concession for salt extraction in Lera from Droga Portorož, founded the company Soline, pridelava soli d.o.o., reinforced the salt story based on historical facts and created the Piranske soline (Piran Salt) brand. Today, the traditional Piran salt and a wide range of salt-related products and souvenirs are sold all over the world. In 2001 Telekom Slovenije acquired a 20-year concession for the management of the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park.

In 2014, Piran Salt was registered in the European Union as a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) (Commission 2014). The designation is linked to the specific geographical environment that includes natural and human factors: climate, soil quality, local knowledge and experience. In 2015, on the initiative of the Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum Piran, the company Soline pridelava soli, d.o.o. and the public institution the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park, the traditional production of sea salt was granted the status of intangible cultural heritage in the Slovenian National Register. The status was awarded on the grounds that the Sečovlje salt pans, along the Strunjan salt pans, are the only existing and functioning salt pans of the so-called “Venetian type” with the island of Pag technology of salt production in the northern Adriatic region. Almost six decades after the abandonment of the medieval or family method of salt extraction, only a handful of living salt producers still know and master this process. The peculiar technology and terminology associated with the salt extraction method, which have survived only in the Fontanigge area, are under threat. Despite the technological modernisation in the Austro-Hungarian period over 100 years ago, salt production in Lera and the Strunjan salt pans is still based on the processes of petola preparation and preserves the traditional manual harvesting of salt. The continuation of the centuries-old tradition of salt production contributes to the memory of an important element of the economic development of coastal communities and the link between the place and the tradition of salt making (2015).

The stories of spa tourism also refer to the past. The use of salt-pan mud and brine for the treatment of skin diseases, also called thalassotherapy, was first introduced by the Benedictines of the monastery of St. Onofrio from Krog above Sečovlje. It existed in the period 1432-1957. Today, thalassotherapy is marketed by the Lera-based company Thalasso Spa Lepa Vida, as well as by some hotels in Portorož and Piran. The development of tourism in Piran began with spa tourism, and Piran is now the leading municipality in Slovenia in terms of the number of overnight stays.

“Appropriation” of salt pans

Several interested parties want to take advantage of the proximity to the salt pans landscape. The Portorož Aerodrome in Sečovlje is competing for space, and a resort is planned on the site of the disused Sečovlje black coal mine, which was in operation between 1935 and 1973 right next to the salt pans. There is also a golf course nearby.

Today, the history of salt is incorporated wherever possible in the tourist neighbourhood. Salt production and the salt pans landscape are presented to tourists or visitors through old and contemporary photography, through urban sculpture and in a particularly illustrative way on the occasion of the Saltworks Festival. This used to take place around St. George’s Day, April 23, to mark the departure of the people of Piran for the salt pans, but in recent years it has been held around St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24, when the salt workers finished harvesting salt and returned to Piran. The salt pans landscape is also often used in screenplays or as a set for various films, music videos and commercials (Topole and Pipan 2022).

Salt pans (heritage) – management issues

The importance of salt pans has been constantly changing over the last decades. While for centuries the economic function of the salt pans was in the foreground, today the nature conservation function is gaining importance in the Fontanigge area. The Sečovlje salt pans are Slovenia’s largest coastal wetland and the most important ornithological and faunistic area, with many species on the Red List of threatened species. In 1993, Fontanigge was the first wetland in Slovenia to be included in the Ramsar List of wetlands of international importance (Ramsar Sites…2023). When Slovenia joined the European Union in 2004, the Sečovlje salt pans and the surrounding area became part of a Natura 2000 protected area (2019; 2021).

The Fontanigge salt pans are threatened today – partly by tectonic subsidence and subsidence in the unrehabilitated abandoned coal mine, but also by rising sea levels due to climate change and lack of maintenance of salt pan dikes or improper management. The main flood control dam along the Dragonja River has not been restored since the Fontanigge salt pans were abandoned. Floods threaten the foundations of the four restored salt-pan museum houses, and even more so the remaining, unmaintained ruins, the last examples of temporary salt-pan dwellings. One of the Museum’s two salt fields is constantly flooded, and the wind pump functions only to a limited extent. The inadequate status of the Museum of Salt Making is the cause of its deterioration. It does not have the conditions for salt extraction. The state concession belongs only to the company Soline pridelava soli d.o.o., which is also the manager of the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park. It also manages and maintains the two salt fields of the Museum. The entrance fees to the park are now uniform and are the responsibility of the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park. The Museum no longer collects entrance fees, issues admission tickets or keeps visitor statistics. The spatial separation of the Lera and Fontanigge areas is also an obstacle. The Fontanigge area is only accessible to bicyclists, visitors who arrive by a small electric tourist train and pedestrians who enter through the secondary entrance of the park. This has led to a drastic drop in the number of visitors to the Museum of Salt Making, from 25,000 in 2005 to 3,000 in 2019. Previously, the Museum was able to finance itself through the proceeds from the sale of souvenirs and its own salt, produced in a way that has not changed since the Middle Ages. The open-air Museum of Salt Making no longer has any real function; only the four museum houses remain under the management of the Museum.

In other salt pans, salt workers stayed at the edge of the salt pans, but here, in the northernmost salt pans of the Mediterranean, where the weather can change quickly, their constant presence in the middle of the salt pans was crucial to protect the brine from sudden rains as quickly as possible. A map of the Sečovlje salt pans from the mid-19th century shows 493 salt pan houses, on the 1984 map there are 118 (Križan 1990), and in 2019 only 70 salt pan houses remain as ruins. The Fontanigge area was already transformed into a “deserted landscape” in the period 1967–1991 (Mares, Rasin, Pipan 2013).

In order to find a suitable way to protect the ruins, Outsider magazine, a Slovenian magazine focusing on culture and society, published the “Salt-pan house” competition (Granda 2020) at the end of 2019 and brought together the stakeholders responsible for the management of the salt pans (Granda 2021) in the Centre for Creativity Partnership Network ([[Center za kreativnost 2020]g). The competition sought “proposals for the design of a temporary spatial installation in a selected ruin that would protect one of the former salt-pan houses from further deterioration, intervene in it with contemporary architecture and at the same time allow for expert reflection on a more appropriate use” ([[Granda 2021]g). Of the 252 proposals received from around the world, the first prize-winning project is a reminiscence of the seemingly inexorable decay of the site, posing a polemical question to the visitors. The second-place project is a transformative strategy tailored to the selected ruin. Instead of reconstruction, it proposes a radical protective construction which, with appropriate adjustments, could also serve as a model for the protection of other ruins (2020).

Thus, there are many conflicting interests in the Sečovlje salt pans. Some see the inscription of the salt pans and the town of Piran on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a solution to their fate – a formal initiative for inscription on the UNESCO test list was already taken in 2012 by the Institute of Mediterranean Heritage of the University of Primorska, the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park, the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Piran, the Municipality of Piran, and representatives of the Ministry of Culture (Šuligoj 2013), while others warn of overcrowding in the area due to increasing numbers of visitors (Carroll 2017).

Protected area

Landscape is a complex phenomenon that combines past and present functions, ideologies and physical connections and influences the formation of people’s consciousness, ideas, emotions, identity… (Moore 1999). It can be understood as a collection of records of a series of historical phenomena, where traces of different time periods can still be seen (Vervloet 1986; Urbanc et al. 2004).

Harvey and Waterton (2015) distinguish between natural landscapes protected as heritage by the interests of colonists or later settlers and those of indigenous peoples associated with their knowledge. The former emphasize materiality and visuality characteristic of Eurocentric conceptions, while the latter emphasize immateriality, experimentation and emotionality (Harvey 2015). Following the example of Clarke and Waterton (2015), the 700-year-old practice of medieval salt extraction in the Fontanigge area can be seen as a system of indigenous knowledge. It is embodied by the Museum of Salt Making, which together with the centuries-old salt fields forms a cultural heritage unit according to the current Slovenian conservation classification, and the wider area is protected as a natural value. In the past, the Museum of Salt Making successfully carried out the heritagisation of the medieval salt production. In 1990, the Institute for the Protection of Natural and Cultural Heritage of Piran designed the Museum in terms of what Harvey and Waterton (2015) call “coexistence of natural and cultural heritage”. The Museum was installed on the abandoned Fontanigge, a peripheral area where it would be unobtrusive to the tourist development of what is otherwise Slovenia’s most touristically developed municipality in Slovenia. The area without modern infrastructure, located in a functional exclave right on the Croatian border (Pipan 2008) and accessible only by a narrow gravel road, has developed over time into a hotspot of biodiversity and natural heritage.

In the case of the Fontanigge area in the Sečovlje salt pans, the cultural heritage (the museum) is subordinated to the “new nature”. The increasing importance of nature conservation or biodiversity protection and the reference to legislation in this field have left the Museum of Salt Making overlooked. While in the Netherlands new nature has been systematically introduced since the 1990s (Spek et al. 2006, 334), in the Fontanigge area new nature has emerged spontaneously.

In Slovenia, a single organisation was responsible for nature and culture protection in the former Yugoslavia, but after Slovenia’s independence in 1991, the two areas were separated. The distinction between natural and cultural heritage is, of course, entirely artificial and, as conservationist Phil Sullivan, a member of Australia’s Ngiyampaa Aboriginal people and an employee of an Australian national park, argues, is unique to white immigrants (Harrison 2015, 30).

The Nature Conservation Act of 1999 (Zakon 1999) established the Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature Conservation. This distinguishes between national, regional and landscape parks among the larger protected areas of high ecological, biotic or landscape value. In Slovenia, landscape parks are the most common type of large protected areas and the result of a long-standing relationship between man and nature (IUCN category V). There are 44 of them in total, covering 5.7% of the Slovenian territory. However, since the field of landscape policy in Slovenia is not yet regulated, there is neither an organised form of protection, planning and management of landscapes, nor a regulated terminology for it. As a result, there is confusion in this area in many places (Topole and Pipan 2022).

In the absence of coexistence between the fields of nature conservation and culture, the Museum has become a hidden narrative about the heritagisation of the landscape of the Sečovlje salt pans. The conflict of interests between the various users of the landscape is becoming evident. The dominant heritagisation narratives are the Piran salt brand on the one hand and the natural values of the Sečovlje salt pans on the other. They lead to a popular romantic notion of the ruins of the salt pans, which are inexorably decaying and becoming fewer every year. The protection of a part of the former “sea salt factory” Fontanigge, is prevented; the Museum of Salt Making is a completely overheard “voice of the locals and non-elites” (Harvey and Waterton 2015) in the middle of Europe.

Parks in Slovenia today serve primarily to protect endangered animal and plant species, but their management should certainly take into account other landscape features as well. The story of a landscape consists of interconnected stories of its natural and cultural heritage. The way park values are managed in the future will determine which area will dominate the landscape of the Sečovlje salt pans.

References

- Benčič Mohar, E. 1992: Obnova solinske hiše [Renovation of a Salt-pan House]. Muzej solinarstva, katalog št. 7. Pomorski muzej “Sergej Mašera” Piran.

- Bonin, F. 2016: Belo zlato krilatega leva: razvoj severnojadranskih solin v obdobju Beneške republike [White gold of a winged lion: Development of the northern Adriatic salt pans during the Venetian Republic]. Pomorski muzej “Sergej Mašera” Piran.

- Carroll, L. 2017: Overtourism at UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Ethical Traveler (8. 11. 2017) Internet: https://ethicaltraveler.org/2017/11/overtourism-at-unesco-world-heritage-sites/ (12. 4. 2021).

- Center za kreativnost. 2020: Partnerska mreža CzK [Centre for Creativity, Partnership Network]. Internet: https://czk.si/program/partnerska-mreza-czk/ (15. 3. 2021).

- Clarke, A., Waterton, E. 2015: A Journey to the Heart: Affecting Engagement at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Landscape Research 40-8, 971–992. DOI: 10.1080/01426397.2014.989965

- Commission implementing regulation (EU) No 436/2014 of 23 April 2014 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications [Piranska sol (PDO)]. Official Journal of the European Union L 128-62, Volume 57. 30 April 2014. Internet: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0436&from=EN

- Granda, N. 2020: Competition: Salt-pan house – Final report 28. 2. 2020. Internet: https://outsider.si/competition-salt-pan-house-final-report/ (16. 2. 2021).

- Granda, N. 2021: Ujeta dediščina [Trapped heritage]. Internet: https://outsider.si/dediscina-med-neoliberalci-in-paraziti/ (16. 1. 2021).

- Harrison, R. 2015: Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene. Heritage & Society 8-1, 24–42. DOI: 10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036

- Harvey, D. C, Waterton, E. 2015: Editorial: Landscapes of Heritage and Heritage Landscapes. Landscape Research 40-8, 905–910. DOI: 10.1080/01426397.2015.1086563

- Harvey, D. 2015: Landscape and heritage: trajectories and consequences. Landscape Research 40-8, 911–924. DOI: 10.1080/01426397.2014.967668

- Kaj je Natura 2000 [What is Natura 2000]. 2021. Internet: https://www.arso.gov.si/narava/natura%202000/ (21. 6. 2021).

- Križan, B. 1990: Preobrazba Sečoveljskih solin ter varstvo naravne in kulturne dediščine [Transformation of the Sečovlje Salt Pans and conservation of natural and cultural heritage]. Primorje: zbornik 15. zborovanja slovenskih geografov. Zveza geografskih društev Slovenije.

- Mares P., Rasin R., Pipan P. 2013: Abandoned Landscapes of Former German Settlement in the Czech Republic and in Slovenia. Cultural Severance and the Environment. Environmental History 2. Springer. 289–309. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-6159-9_20

- Moore, D. K. 1999: Holdfast: At home in the natural world. The Lyons Press.

- Natečaj Solinarska hiša: končno poročilo [Competition: Salt-pan house ]. (28. 2. 2020). Internet: https://outsider.si/natecaj-solinarska-hisa-koncno-porocilo/ (4. 6. 2021)

- Odlok o razglasitvi Krajinskega parka Sečoveljske soline [Decree on the Sečovlje Designated Landscape Area]. Uradne objave občin Ilirska Bistrica, Izola, Koper, Piran, Postojna in Sežana. Primorske novice, št. 5, 26. 1. 1990.

- Odlok o razglasitvi Muzeja solinarstva za kulturni spomenik državnega pomena [Decree declaring the Museum of Salt Making a cultural monument of national importance]. Uradni list Republike Slovenije, 29/2001, pp. 3150.

- Pahor, M., Poberaj, T. 1963: Stare Piranske soline [Old Piran Salt Pans]. Mladinska knjiga.

- Pahor, M. 1972a: Solinarski skansen [Saltworks skansen].

- Pahor, M. 1972b: Solinarski skansen. Turističnim in kulturnim delavcem v razmislek [Saltworks skansen. For tourist and cultural workers’ consideration]. Obala 14.

- Pipan P. 2008: Border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia along the lower reaches of the Dragonja River. Acta geographica Slovenica 48-2, 331–356. DOI: 10.3986/AGS48205

- Ramsar Sites Information Service, Sečoveljske soline. https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris-search/Se%25C4%258Doveljske%2520soline?pagetab=0 (29. 3. 2023).

- Ravnik, M. 1992: Od zamisli do pričetka obnovitvenih del [From the idea to the start of restoration work]. Muzej solinarstva, katalog št. 7. Pomorski muzej “Sergej Mašera” Piran.

- Savnik, R. 1951: Solarstvo Šavrinskega primorja [Le salinage à la côte slovène de l’Adriatique]. Geographical Bulletin 23.

- Savnik, R. 1965: Problemi Piranskih solin [Les problèmes des salines de Piran]. Acta geographica Slovenica 9.

- Spek, Th., Brinkkemper, O., Speleers, B. P. 2006: Archaeological Heritage Management and Nature Conservation, Recent Developments and Future Prospects, Illustrated by Three Dutch Case Studies. Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek 46. Rijksdienst voor Archeologie, Cultuurlandschap en Monumenten.

- Šuligoj, B. 2013: Svetovni spomenik, ki je zrasel na soli. Slovenska kandidatura za Unescov seznam Krajinski park Sečoveljske soline in Piran do sredine februarja že na preizkusnem seznamu? [A world monument that grew out of salt. Slovenia’s candidacy for the UNESCO list, the Sečovlje Salt Pans Designated Landscape Area and Piran on the test list already by mid-February?] Delo. (25. 10. 2013).

- Topole, M., Pipan, P. 2022: Prilaščanje Sečoveljskih solin: trženje naravne in kulturne dediščine [The appropriation of the Sečovlje saltpans landscape: natural and cultural heritage]. Geographical Bulletin 94-1, 115–134. DOI: 10.3986/GV94106

- Tradicionalno pridelovanje morske soli [Traditional sea salt cultivation], 2015: Opis enote žive dediščine, EID: 2-00042. Republika Slovenija, Ministrstvo za kulturo. Internet: https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MK/DEDISCINA/NESNOVNA/RNSD_SI/Rzd-02_00042.pdf (21. 6. 2021).

- Urbanc, M., Printsmann, A., Palang, H., Skowronek, E., Woloszyn, W., Konkoly Gyuró, É. 2004: Comprehension of rapidly transforming landscapes of Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th century. Acta geographica Slovenica 44-2, 101–131. DOI: 10.3986/AGS44204

- Uredba o Krajinskem parku Sečoveljske soline [Regulation on the Sečovlje Saline Landscape Park]. Uradni list Republike Slovenije 29/2001, pp. 3106.

- Vervloet, A. 1986: Inleiding tot de historische geografie van de Nederlandse cultuurlandschappen. Pudoc Wageningen.

- Zakon o ohranjanju narave [Nature Conservation Act]. Uradni list Republike Slovenije 56/1999.

- Žagar, Z. 1992a: Muzej solinarstva [Museum of Salt Making]. Muzej solinarstva, katalog št. 7. Pomorski muzej “Sergej Mašera” Piran.

- Žagar, Z. 1992b: Kako je deloval solni fond v starih Piranskih solinah [How the salt fund operated in the old Piran salt pans]. Muzej solinarstva, katalog št. 7. Pomorski muzej “Sergej Mašera” Piran.