Living with Šavrinka

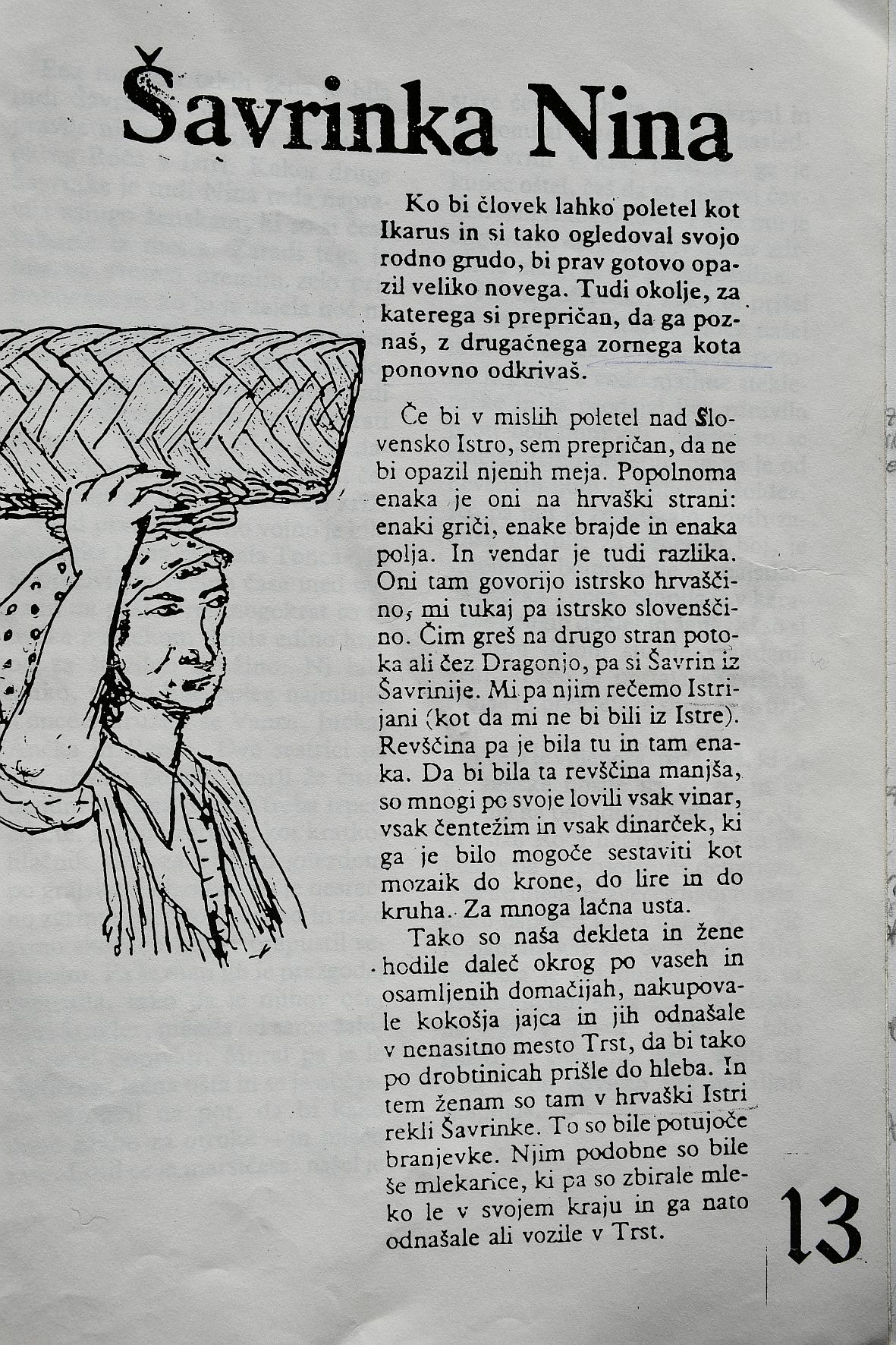

When, one September evening in 1994, we met Mrs. Tonina Vidali in Škofije, a woman who had travelled to central Istria for eggs in the period between the world wars, we recorded our first interview on the topic of migrant women workers in Istria almost twenty years ago, and we were given a copy of a story entitled Šavrinka Nina. This story was introduced by author, Rafael Vidali, with the thought: “If a man could fly like Icarus and look down at the birthplace that was once his, he would certainly notice much that is new. Even surroundings you are certain to know, are rediscovered when seen from a different point of view.” After the interview, Mrs. Vidali and her son Rafael referred us to other egg resellers from the surrounding area, to their family members and friends, reminded us of the novels by author Marjan Tomšič, who wrote about the Šavrinkas, of articles by publicist Milan Gregorič, the work of sculptor, Jože Pohlen, creator of the imposing stone sculpture in Hrastovlje, the poems of the Kubed-born poet, Alojz Kocjančič, and various Istrian cultural and artistic societies and choirs. Clubs, individuals, characters from books and theatrical performances each, in their own way, discover something new, incorporate the everyday local past of rural Istria into their stories. A few built their work on family memories and ties, others on research or personal interests. Although there was a peculiar appropriation of the local past taking place before our eyes, from which emerged a woman, trader, migrant worker, inhabitant of the Istrian hinterland of today’s Slovenian part of the Istrian peninsula, who in the early 20th century resold eggs and other items between central Istria and coastal cities, at that time only a few people talked about Šavrinkas.

In fact, that September evening, we probably witnessed the beginnings of the heritage-making of the Šavrinkas. Heritage-making, made possible and dictated by the changed socio-political circumstances of the second half of the 20th century. After the breakup of Social Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991, in the broader picture of the Mediterranean, a new state border between Slovenia and Croatia sliced through the coastal and near-coastal areas of Istria, bringing an invasion of market-ownership; terraced multicultural cultivated areas were replaced by a monocultural tourism economy, technological development and mobility flooded that world and become fashionable, desirable, even demanded. In such a world, simultaneously connected and separated, Šavrinka – a metaphor for the strong and mobile woman from the present-day Slovenian part of Istria – became Istrian and national heritage.

What exactly is heritage, when does it become obvious and what does it mean to live with heritage, in our case, to live with Šavrinka? The simplest definition of heritage is something that is from the past (tangible or intangible – it can, for example, be a vase, a building, a song or the skill of making a certain cheese, to name a few), and which today has important recognition, is worthy of preservation, as something that enriches us, that we would like to pass on to the future, to our descendants, and also something that connects us. Not everything from the past, however, by a long way, is heritage. One of the important properties of heritage is exclusion. In Istria, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and in the first half of the 20th century, women’s (and men’s) work migration associated with reselling various items was a widespread economic activity, but today, above all, Šavrinka stands out in the context of heritagisation processes. To understand why, let’s look at the story of the Šavrinkas and other Istrian traders in the broader historical perspective of Istria.

Women’s labour migration in the first half of the 20th century in Istria and the popularization of the Šavrinkas today

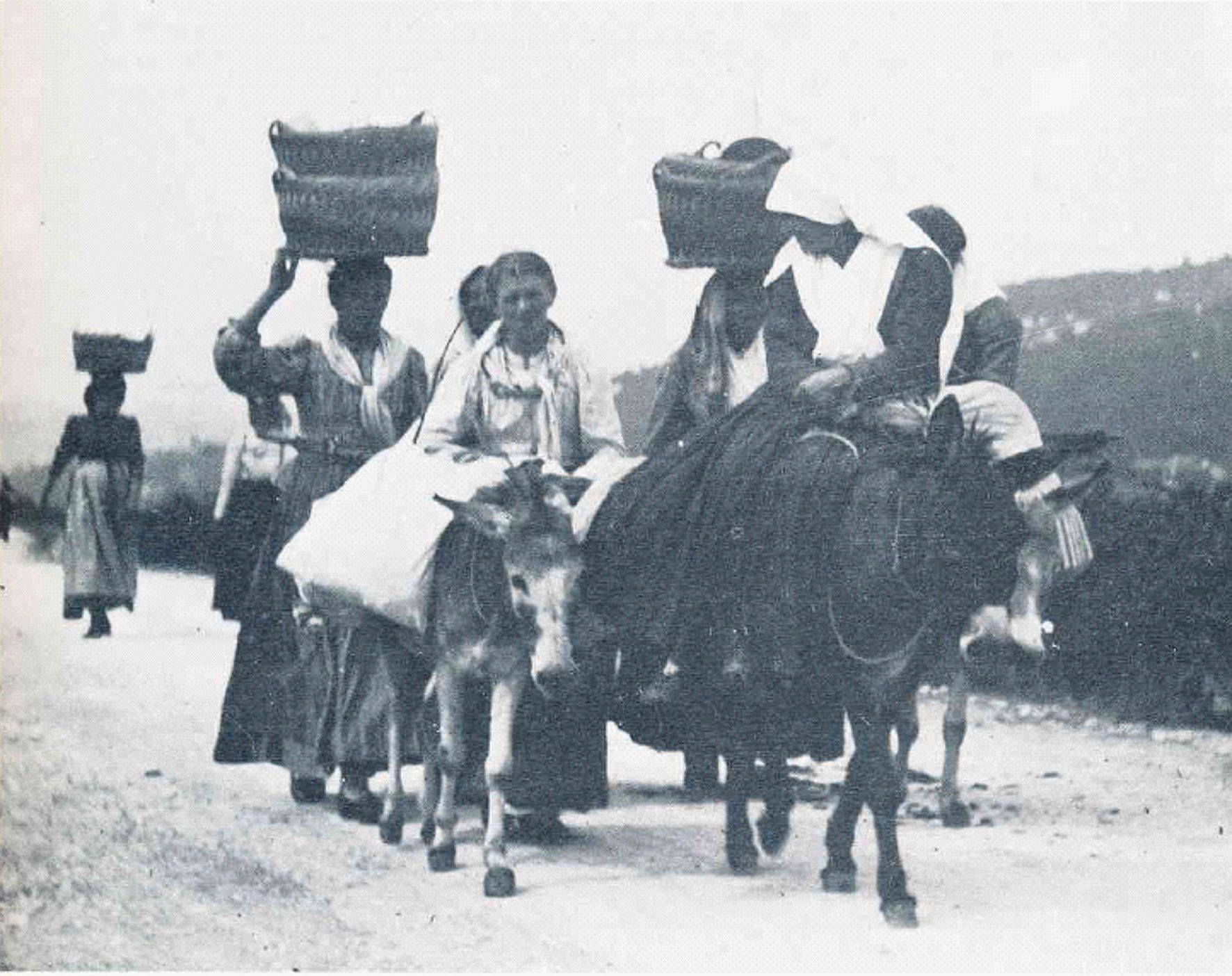

The dominant characteristic of Istria in the first half of 20th century was its lack of economic development and delayed industrialization, coupled with transoceanic as well as seasonal and weekly migration of workers to coastal towns. The majority of its population worked in agriculture, where most of the fertile land was held by a few farmers, and the smaller, fragmented, largely infertile and less easily reachable plots were left to everyone else. Frequent changes of political systems, large families, wars and marginalization of the predominantly rural – Slovene and Croatian speaking – population of Istria all contributed to poverty, a sense of social exclusion and helplessness (in terms of influencing the given situation). In such circumstances, trading, or rather smuggling, goods and merchandise between the rural and urban parts of the region – occasional small contraband commerce, as such – became the primary source of income not just for individuals, but also families, even entire villages. In the mosaic of Istria’s work migrations it was the women (re)sellers who played the most significant role, and who, in a time of war and poverty, effectively became the key providers for their families. Such semi-legal economic tactics were a common survival strategy, as well as an exit route in those times of need dictated by crises.

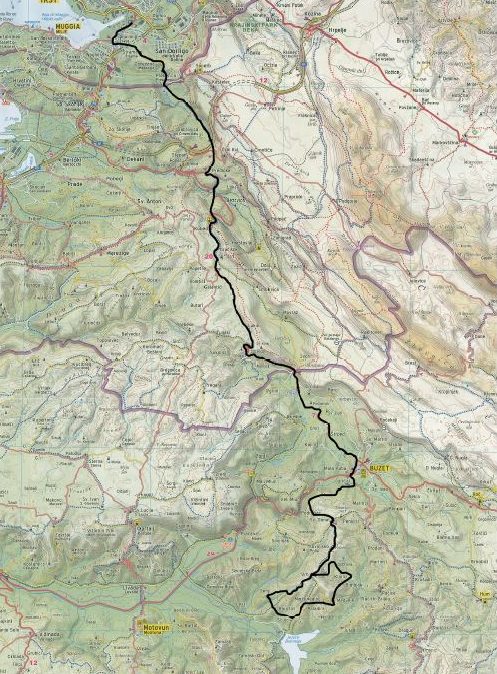

Many a story has carved the routes leading from the countryside to coastal towns encompassing Istrian cargo carriers, traders, smugglers, and travellers; alongside milkmaids from the northern parts of Istria, bakers, cakemakers, shepherds and wood traders, there were also garlic traders from Moščenice and Brseki, and potters from Raklje, Oprtal and Hum, stonemasons from Kastavje and many other traders who would sell their produce, wares and services in the towns of Istria. One such story is the trading route taken by the Šavrinkas, who sold eggs between central Istria and Trieste in the period between the end of the 19th and the middle of the 20th centuries. The Šavrinkas came from the towns between the Pregar plateau and the Karstic rim; from the villages of Kubed, Gračišče, Dol, Hrastovlje, Truške, Trsek, Boršt, Nova vas, Sveti Peter, Lopar, Marezige and Pomjan. They carried various items bought in the shops of Trieste (thread, cloth, soap, petroleum, pepper…) to central Istria, for which they were paid in eggs. They would then carry the eggs on a weekly basis to the Trieste markets, and make a small profit by selling them there. The round trip between the home village, Buzet or Motovun, and Trieste, lasted between three to four days, and the sellers would undertake it weekly.

The name, and then common term, for the egg sellers of central Istria thus became Šavrinkas. The inhabitants of present-day Croatian part of the Istrian peninsula say it is because they were from the Šavrinija region. The women egg sellers from Gračišče and Kubed did not self-identify as Šavrinkas, and it was through contact with the people of central Istria that they came to know about this ethnic identification, which they subsequently internalized. The designation gradually acquired a professional connotation throughout the second half of the 20th century, but with the disappearance of the egg trade and in the context of the emerging new state border between Slovenia and Croatia and an increase in tourism, Šavrinka acquired new symbolic connotations linked to tradition, authenticity, Slovene Istria, and so on. As one of the sellers put it: “We had no idea we were Šavrinkas. Now we are all Šavrins.”

Local theatre groups, books, borders and tourism

Our field work in Istria in the early 1990s thus encompassed a time when interest in the former everyday life of the Istrian hinterland was something usual. And just as our first informant wanted to fly like Icarus and look at his birthplace from a different angle, it was this browsing, discovering and re-establishing the past from a new perspective that was actually taking place before our eyes. Women migrant workers and the image of the Šavrinkas were an important part of this discovery (also academic!) and it was not difficult to find people who were willing to talk about the Šavrinkas. In the following passages, we look at why, over a period of time, the Šavrinkas and their families opened up and how it all combined into a mould of heritage.

Just as the Šavrinkas stand with one foot in older ethnic denominations and the other in popular imagery, the women who traded between central Istria and the coastal towns were, and (still) remain, torn between various perspectives, possibilities and attributes. The egg resellers experienced the disappearance of cyclical times and the transition to the modern society of the second half of the 20th century; in their youth they felt the difficult role of women, the ambivalent attitude towards women’s mobility, and in the second half of the 20th century the emancipation of women; they survived poverty and experienced a sense of inability to influence the situation, and later the material comforts of modern society; they watched different political regime changes and wars that required flexibility; they experienced the emergence of new borders between the Kingdom of Italy and Yugoslavia, between Yugoslavia and Zones A and B, and later the Free Territories of Italy, and finally the border between Croatia and Slovenia. The second half of the 20th century was also experienced as enthusiasm for the Mediterranean, for mobility, the “authenticity” of rural Istria; and eventually the transfer and popularisation of the Šavrinkas in novels, the fine arts, folklore performances, museum and amateur collections and tourist materials. Not surprisingly, those migrant women workers, who travelled between 125 and 170 km a week, became marginalised, suffered injustice, poverty and the division between children and other obligations, wanted to talk about their experiences.

Most avidly recounted are the tales of Marija Franca, a former egg-carrier, folk writer, author of three books Šavrinske zgodbe [Šavrinkas stories], the informant and landlord of the writer Marjan Tomšič and our informant. Marija’s stories are written from her own experiences and memories; her circumstances were specific, she was the widow and mother of four children; her most vital years were spent trafficking between central Istria and Trieste. She was a passionate reader, curious and inquisitive, so she liked to befriend with teachers and intellectuals. Although her life was specific, many saw themselves through her story. Not because it was an accurate portrayal of the truth, since memory is always selective, and also not because it exactly matched the fates and paths of other Istrian traders, but because it appeared at the right time and because she portrayed the honest and humorous confession of an “authentic” egg-carrier. Remembrance and appropriating the past is not (necessarily) a search for the truth, but a story tailored to the present time and space that finds its listeners.

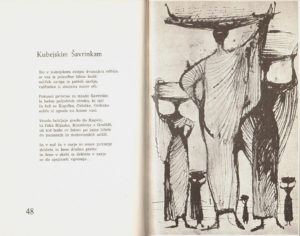

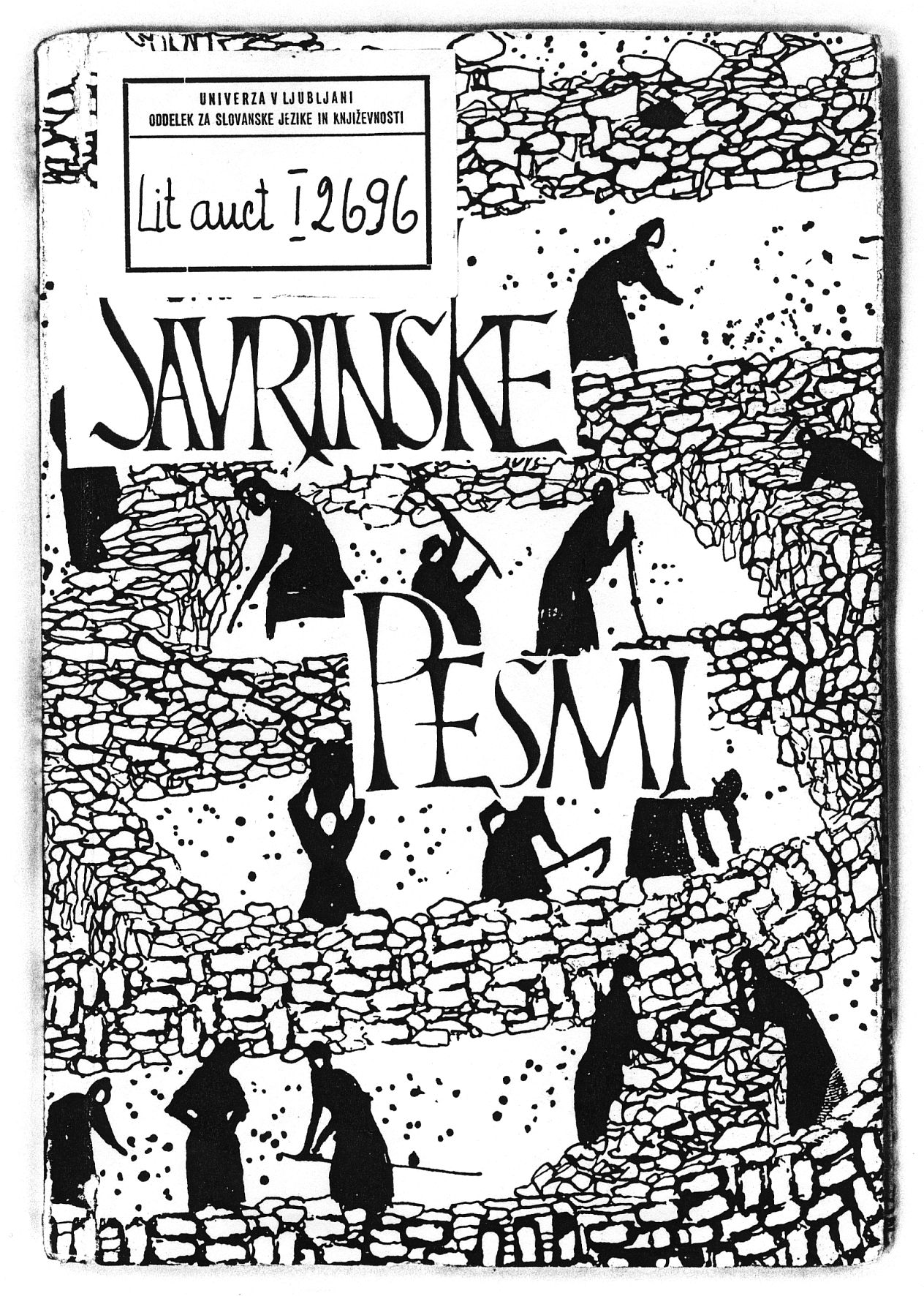

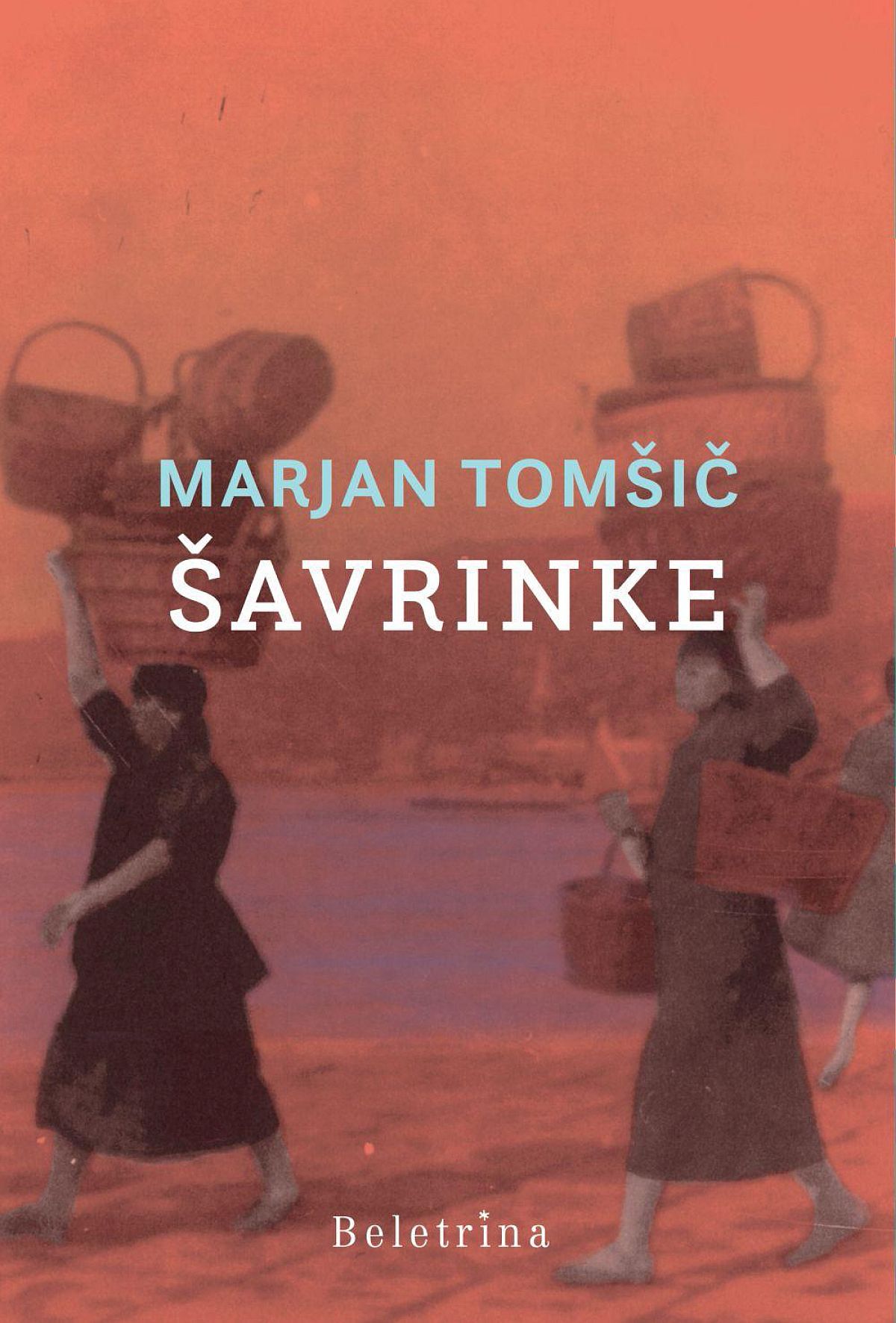

The process of heritage-making, however, goes even further. Heritage needs institutions and professionals who recognize, protect, preserve and display it with a timely message. And in the case of the Šavrinkas, a great deal of the recognition and positive opinion of the traders between Istria and Trieste was undoubtedly to do with artists. The Šavrinkas became an artistic motif for celebrated Slovenian artists, and became empowered through their works. The first was the local poet Alojz Kocjančič, who in a collection of Šavrinske pesmi [Šavrin Poems] (1962) dedicated two poems to these women, the Kubejskim Šavrinkam [To the Kubed Šavrinkas] and Materi [To Mother]. Most notable were the novels by Marjan Tomšič, especially The Šavrinkas, which was reprinted several times, most recently in 2019. In the fine arts, the Šavrinkas have been depicted by Jože Pohlen, most prominently with his monumental statue of the Istrian woman in Hrastovlje, which was later renamed Šavrinka (Ledinek Lozej and Rogelja 2012).

Artists, however, were not the only ones to consider the Šavrinkas. Even during Marija Franca’s life, the Šavrini inu anka Šavrinke local cultural association began staging stories from Marija’s Šavrinske zgodbe. The performances brought Marija’s stories to life; where the actors recreated and replayed, the spectators saw their past.

Almost every house in Istria had a mother, aunt, grandmother, sister or cousin who either went to trade eggs or to work in Trieste, keeping the household together, as we often heard, and, at the same time, had to confront the prejudice of the then dominant patriarchal societies in the first half of the 20th century. This is how the then president of the society, Marija Knez, described the beginnings of the theatre group, which dates back to the 1980s.

Look, we established on the sixth of December, in a garage in Gračišče, because we didn’t even have our own space. I said, since we had performed on Radio Trieste with dialogues from Šavrinske zgodbe, let’s carry on. […] We had a one-hour cultural program in Koper. Now imagine, my (own) people, actors, we were just amateurs. Three of them took part in the theatre for the first time, and not on the seats, but on stage. The first time in a theatre! […] These are not actors, these are people who came to life on stage from a hundred years ago. They come to life and live and act. They act the life they live, that they lived. And it is within them, and they live it again.

Marija Knez, 25th August 1999

Although artistic, especially literary, interventions undoubtedly had a great influence on revealing women’s migration in the context of the motifs of magical Istria, women’s suffering, sacrifice, independence, eroticism, these artistic interventions should not be overestimated. The Šavrinke Choir, founded four years before the publication of Tomšič’s novel, would certainly have been operating without any artistic depiction. Local collectives and other cultural societies, through their own performances, have emphasized the active roles that women played in their past and present roles. The story of the traders was evocative to the extent that, in addition to remembering, it also enabled creative reproduction. Reproduction, which is key to the making of intangible heritage (Smith and Akagawa 2009; Hafstein 2018). This is how the creative work of the Šavrini in anka Šavrinke [Šavrins and also Šavrinkas] cultural association was described by the then president:

Glue, flour, newspaper… And we made these masks and it really was all original. With (all) this we appeared in Portorož… and everywhere, we won first prizes. I had such a mask and when I performed with this mask in the main square in Portorož, my cousin Marčelo shouted: “Look, look! Marija Franca has a double.” Like a double, a double of Marija Franca… The silhouette of the Šavrinka often depicted by Pohlen.

Marija Knez, 25th August 1999

In the last decade, the Šavrinkas have bravely descended from the hinterland of Istria to the coast and sailed into the seas of heritage. On the seaside promenade between Piran and Portorož, the Šavrinkas were presented as part of an outdoor photographic exhibition entitled Male štorije naše dediščine [Little stories of our heritage]. The exhibition was designed by the society Anbot Piran [Once Piran] as part of the European Heritage Days. The scenes, set as staged ambiences, were photographed by Ubald Trnkoczy.

The Šavrinkas also appear en masse on postcards, scaled down and neatly placed in the windows of many coastal souvenir shops, invited to celebrate coastal municipal holidays, a renowned Koper publishing house has dedicated an academic monograph to them (Celestina and Todorović 2017), and, at the time of writing, one local tourist agency is offering a thematic excursion following the Šavrinka routes. Confident performances also appear online, as part of the cultural heritage of Slovenian Istria.[1]

In a way, the Šavrinkas reflect a victory of the “authentic”, Slovene, Istrian countryside over the coast, as noted by the anthropologist Bojan Baskar (2002). Throughout history, the hinterland of Istria was associated with a predominantly Slavic-speaking population, while today’s Slovenian coast was associated with the Venetian-speaking population until the middle of the 20th century.

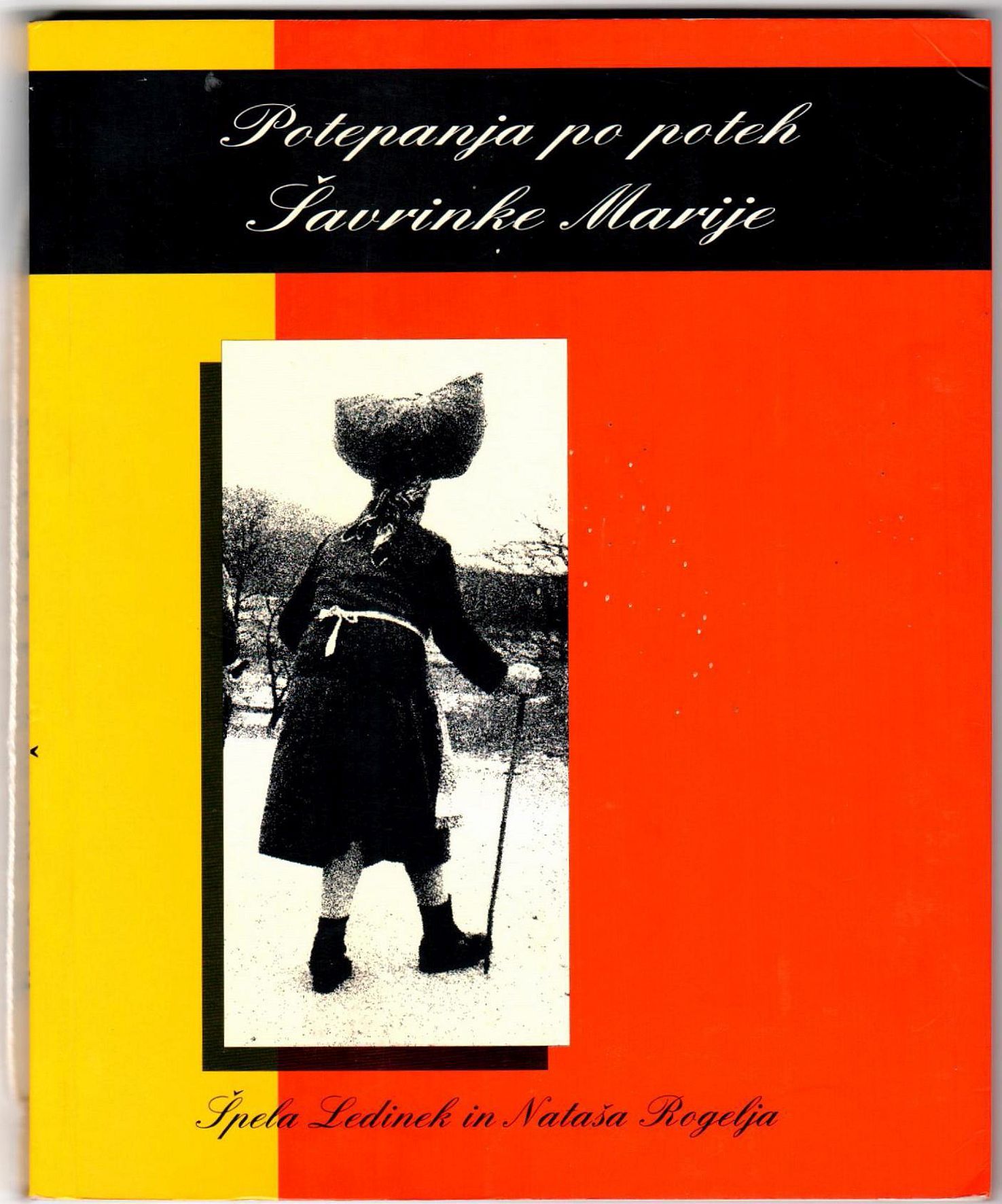

Heritage-making is a process that has cultural, economic and political motives. In order for something or someone to fit the mould of heritage, a local, national, and broader regional, sometimes even global accord is required. And in the heritage-making of the Šavrinkas there has undoubtedly been successful accord: first, the historically grounded difference between the Slavic rural hinterland and the Venetian urban coast; secondly, the newly formed border between Slovenia and Croatia in 1991, as a result of which the Šavrinkas became a convenient representative of the Slovenian Istria; third, the Šavrinkas became a motif for artistic expression; fourth, it arose from a set of local memories and the local initiatives of present-day individuals and cultural societies. Finally, in the process of the Šavrinkas becoming heritage, more than a hundred kilometres of trade routes also became important, which created great interest during a period of accelerated development in tourism, recreation and hiking. Last but not least, we were also involved – as the ones who followed one of the traders footpaths as part of this research, photographically documented it and lastly wrote and presented it in a book, Potepanja po poteh Šavrinke Marije [Wanderings on the Paths of Šavrinka Marija] and in an ethnographic exhibition of the same name. We have all added our pebble to the mosaic of the present-day Šavrinkas.

And today?

The Šavrinkas have outgrown the local Istrian context and become national heritage. They are much liked by (international) tourists. A brave independent woman from the past of today’s Slovenian Istria, who walked more than a hundred kilometres a week on her round trip trading route – what is not to admire! We often heard about the occasional jokes of men suggesting how difficult it was to live with a Šavrinka. Today, as we observe it from afar, distorted by time and space, it may be easier. Or maybe it just seems that way.

Del neobjavljenega zapisa Šavrinka Nina iz terenskega dokumentarnega gradiva Nataše Rogelja in Špele Ledinek Lozej.

References

- Baskar, B. (2002a). Med regionalizacijo in nacionalizacijo: Iznajdba šavrinske identitete [Between regionalisation and nationalisation: The invention of the Savrinian identity]. Annales: Series historia et sociologia 12(1), 115–132.

- Baskar, B. (2002b). Dvoumni Mediteran: Študije o regionalnem prekrivanju na vzhodnojadranskem območju [The Ambiguous Mediterranean Studies of Regional Superposition in the Eastern Adriatic]. Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko, Znanstveno-raziskovalno središče Republike Slovenije

- Brumen, B. (1996). The State want it so, and the Folk cannot do anything against the State anyway. Narodna umjetnost, 33 (2), 139–155.

- Brumen, B. (2000). Sv. Peter in njegovi časi: Socialni spomini, časi in identitete v istrski vasi Sv. Peter [Sv. Peter and its times: Social memories, times and identities in the Istrian village of Sv. Peter]. Založba /*cf.

- Celestina, I. and Todorović, S. (eds.) (2017): Šavrinka [The Šavrinka]. Libris.

- Franca, M. (1990). Šavrinske zgodbe [The Šavrini stories]. Fontana.

- Franca, M. (1992). Šavrinske zgodbe 2 [The Šavrini stories 2]. Fontana

- Franca, M. (1995). Šavrinske zgodbe 3 [The Šavrini stories 3]. Fontana.

- Hafstein, V. Tr. (2018). Making Intangible heritage: El condor Pasa and other Stories from UNESCO. Indiana University Press.

- Ledinek, Š. and Rogelja, N, (1997). Šavrinka kot oseba in simbol [The Šavrinka as a person and as a symbol]. Etnolog, 7, 131–145.

- Ledinek, Š. and Rogelja, N. (2000). Potepanja po poteh Šavrinke Marije [Wandering along the paths of Šavrinka Marija]. Slovensko etnološko društvo.

- Ledinek Lozej Š. and Rogelja, N. (2012). Šavrinka, Šavrini in Šavrinija v etnografiji in literaturi = The Šavrinka, Šavrin, and Šavrinija in ethnography and literature. Slavistična revija, 60 (3), 537–560.

- Ledinek Lozej Š. and Rogelja, N. (2014). Vloga preprodajalk med osrednjo Istro in obalnimi mesti z začetka 20. stoletja v procesih regionalizacije in nacionalizacije Istre [The role of the woman traders between central Istria and coastal towns from the beginning of the 20th century in the processes of the regionalisation and nationalisation of Istria]. In Belaj, M. et al. (ed.), Ponovno iscrtavanje granica: Transformacije identiteta i redefiniranje kulturnih regija u novim političkim okolnostima: 12. hrvatsko-slovenske etnološke paralele = Ponovno izrisovanje meja: Transformacije identitet in redefiniranje kulturnih regij v novih političnih okoliščinah: 12. slovensko-hrvaške vzporednice, (109–125). Hrvatsko etnološko društvo; Slovensko etnološko društvo.

- Ledinek Lozej Š. (2014). Šavrinke – preprodajalke med osrednjo Istro in obalnimi mesti ter nosilke simbolnih identifikacij: Družbenozgodovinske okoliščine delovnih migracij in šavrinizacije istrskega podeželja [Šavrinkas – migrant Women traders between central Istria and Coastal Towns and Bearers of Symbolic identifications: Sociohistorical Conditions of Labour Migrations and the “Šavrinization” of the Istrian Countryside]. Dve domovini, 40, 47–55.

- Ledinek Lozej Š., Rogelja, N. and Kanjir, U. (2018). Walks through the multi-layered landscape of Šavrinkas’ Istria: eggs, books, backpacks and stony paths. Landscape Research 43 (5), 600–612. DOI: 10.1080/01426397.2017.1336207.

- Rogelja, N. (2014). Vse po resnici: Uporaba biografske metode pri raziskovanju Šavrink [It is all true: The use of a biographical method on Research on Šavrinkas]. Dve domovini, 40, 35–46.

- Smith, L., Akagawa, N. (ed.) (2009). Intangible Heritage. Routledge.

- Tomšič, M. (1986, 1991). Šavrinke [The Šavrinkas]. Kmečki glas; Beletrina.

footnotes

- KD Šavrini in anka Šavrinke ohranjajo narečno in kulturno dediščino [Šavrini in anka Šavrinke preserve dialectal and cultural heritage], Ohranjamo kulturno dediščino [We preserve cultural heritage], Šavrinska književnost [Literature on Šavrinkas], Naravna in kulturna dediščina – Hrastovlje [Natural and cultural heritage – Hrastovlje][↑]