Walking the borders: Between oblivion, memory and history of the Carinthian ravines

Walking seems so natural, commonplace, and such a widespread human activity that it gets little attention.[1] We walk to get somewhere. And yet, between here and there, thoughts, emotions and physical feelings (may) lead to their own kind of renewed notions of the world, a re-understanding that comes close, even if it goes far or at least diverges. For one of the first European walking research attempts, it is worth mentioning Reveries of the Solitary Walker (Fr. Les rêveries du Promeneur Solitaire, 1776-1778) author of the Age of Enlightenment, Frenchman Jean Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau’s text had an impact on many romantic English and German-language authors, echoing both geographically and chronologically far beyond the European cultural centres of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In the following century, the figure of the researcher/walker solidified that outline in fiction and aesthetics (Thoreau 2019 [1862]; Baudelaire 1863; Woolf 1930), as well as in the social sciences and humanistic research. In the last fifty years, predominantly within human geography, and anthropology, researchers have used descriptions of walking to present fieldwork (Selwyn 2012; Rogelja, Janko Spreizer 2017). Some centred their research interests on an understanding of walking as common human practice (Solnit 2001; Ingold, Vergunst 2008; Ingold 2011), or they used ethnographic walks as a specific research methodology (Anderson 2004; Pink 2009; Edensor 2010).

Walking as an ethnographic research approach has also been tested by colleagues from the Heritage on the Margins programme group and the Experiencing Water Environments and Environmental Changes project group. Ethnographic seminars, or walking seminars as we call them, follow the experiments of Nick Shepherd, Professor of Archaeology, Heritage and African Studies at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, and at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and, to some extent, also other attempts at ethnographic and research walks, most notably phenomenological approaches in geography and anthropology, as well as some pioneering approaches within Slovenian ethnology (Ledinek, Rogelja 2000). As Nick Shepherd wrote in the editorial of the publication Walking Seminars: Embodied Research and the Emergent Anthropocene Landscapes (Shepherd et al. 2018), his seminars had three goals: to explore the intersection between conventional science and the art practices, to use walking as a methodology to explore landscape and history, and to re-consider time, materiality, and memory. The main thrust of Shepherd’s seminars is, in fact, to flatten the established hierarchies between theory and empirics, between scholarly research and creative practices, including “playfulness” and “seriousness”. As noted by Shepherd in the above-mentioned publication:

I am thinking of playfulness not as the opposite of seriousness, but as something that exists in a more complex relation to seriousness, even as the index of a special kind of seriousness.

Shepherd 2018: 13

And off we went. We walked with various borders, pressed between oblivion, memory and the history of the shaded Carinthian ravines upon which the sun-kissed peaks of the eastern Karavanke occasionally appeared. Apart from the enthusiasm involved in our small methodological experiment, walking the Carinthian ravines coincided with another important occasion, namely the 100th anniversary of the Carinthian plebiscite. It was at the end of the First World War, in compliance with the program of the then American president, Thomas Woodrow Wilson, on the self-determination of the nations, that the people of the southern province of Carinthia chose whether to be part of Austria or part of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. On the October 10th, 1920, almost 60 % of Southern Carinthia’s electoral voters in Zone A chose to join Austria. Our Carinthian walking seminar did not take place on the 10th October, however, our steps inadvertently marked another historic date, also linked to the previous century: September the 8th, the anniversary of Italy’s capitulation in 1943. But the dates, no matter how important, dissolved into the September greenery of Carinthia and the words of Maja Haderlap, which elicit people’s emotions much more than political facts. Our walking seminar started just there, among the words of the Carinthian writers, taking the first step at home, reading the novel Angel of Oblivion (Ger. Engel des Vegessens) by Maja Haderlap (Haderlap 2011), a lyrical novel describing a difficult subject. We read about Carinthia. The Second World War. And personal stories.

The ups and downs, injustices and losses in pre-, during and post-Second World War, described in the novel, were much harder than the steps along the ravines that followed the reading. A beautiful sunny day and the pleasant guidance of Zdravko Haderlap awaited us in Carinthia and both time and space – for the sake of the guide, the writer and perhaps ourselves – expanded. We walked in the here and now, but also everywhere and beyond that moment. To fully understand and grasp any research area in the temporal and spatial reality of the present moment, we need to call the self-evident boundaries into question. Fieldwork creates its own dimensions. Time, which we traversed through the stories of our interlocutors, was stretching all the way from the Spring of Nations in the 19th century to the winters of the 21st century, melting under the global reach of climate change. Young chestnuts being able to move into the undergrowth of the high forests of Carinthia, in areas where it was previously too cold. How did they get there? In answer to the question Zdravko replied, “supposedly they got carried there by some birds”. As we listened to, and walked first up, then down the wooded slopes, the space also began to spread – from the Carinthian ravines to all of Europe and beyond. And it has often been thought out loud that Europe’s central features, through its bonds and its divisions, is the Second World War. A thick, sticky period. Much like tree resin.

The first stop of our walk was the old public school in Leppen/Lepena, a sports-cultural centre. We were greeted by Willi Ošina, president of the Slovenian Cultural Society “Zarja”. The school has two main spaces, one for sport activities and the other for cultural ones. Before entering the main space, we answer the “call of nature.” The washrooms look so familiar – a tiled floor embellished with tiny brown, red and white stones and door-catches that lock in the “opposite” direction. “Many locked themselves in, and were then unable to get out,” says Willi. We know the “wrong” unlocking system well. School as we knew it – our school, a school of the 1980s. Someone makes a loud comment that these tiny, insignificant toilet door-catches should be protected as a cultural heritage. Preservation is always a matter of perspective. In the first space of the converted school, there are ping-pong tables; fractured portrait s of local authors in the second. Maja Haderlap, Florjan Lipuš, Cvetka Lipuš. “They are bound by a strong sense of justice and anger,” our host tells us.

As we sit in a circle of school desks, our guide Zdravko explains, the rest of us listen and write, here and there, a question asked. We mainly talk about schools. Zdravko gives an outline of the area’s history through the story of schools, which seem to be two-headed dragons. School – church, school – inn, Slovenian school – German school. Both history and landscape appear to be full of virtual, instantaneous and changing contradictions and fractures. Shaded and sunny sides, peaks and ravines, central and marginal, winners and losers. The only way to survive seems to be to combine opposites. And walking on the clouds. “People only used to walk over the peaks of the world, never descending into the valley, then the borders were cut here, the paths changed, the old connections were broken,” explains Zdravko. A ravine of dichotomies, where writers fracture only to reassemble once more. Perhaps literature is able to transcend such limits, walking on the clouds, only hitting rough patches here and there.

On the way to Zdravko’s house, the homestead where he grew up together with his sister Maja, we encounter a landscape installation – a garden with a collection of farm tools and run-down equipment from an abandoned mill. Zdravko hangs them from the tree branches, gives them a special place on the lawn, sets them upright, or in some other position, contrary to the natural order of things, and leaves them to become overgrown. “Decay grows from the outside here,” he says. “[T]he pile of debris before him grows skyward,” wrote Walter Benjamin (1940) in his theses On the Concept of History (Ger. Über den Begriff der Geschichte) (Benjamin 1998). Outward facing disintegration, a spreading decay. Zdravko organises events here. Dance performances with few words. Perhaps the past, the memories and the heritage of this area are easier to dance about.

We are invited to the lovely winter garden of Haderlap homestead, Zone A, as the host calls it, where hot coffee and fruit brandy await us. The walls in the room are printed with pastel-coloured patterns and letters, we sit on the newly restored iconic Thonet chairs from the abandoned Obir Hotel in nearby Železna Kapla/Eisenkappel, precisely like the ones we sat on as children, and we feel at home again. Partisans and Germans, toilet hooks and chairs made of curved and curvaceous wood were those hooks of the past that we had caught ourselves on before the first step.

Photo: Nataša Rogelja Caf, 2020.

Starting up a steep green bank, the strong stink of sheep comes from our left. We stop at the Pečnik homestead that once housed orphans, children whose parents were taken from them by the war. We know the scene from the book. “Nothing special,” says Zdravko, “this place was full of such children. War is not to be interpreted,” says Zdravko, acknowledging Ingeborg Bachmann’s words, “it follows irrational mechanisms, driven by ideologies.” We climb up to the next stop in the middle of the forest, where, among the overgrowth lies the remains of a house, the remains of tale of war massacre. We read a passage from the Angel of Oblivion, we look at the ruins submerged in the overgrowth, we hear birds chirping now and then. “Brains were stuck to the trees.” Cutting words. They were stuck right here, right on the trees that we are leaning against. How does the landscape absorb history? Bullet marks grow within the structure of the trunk, becoming inseparable over the years, the brain slips into the roots. This is how the landscape embraces history. Without words, dissolved in forest tendrils. A humus of history. “A garden that self-renews, three-dimensional literature,” says Zdravko and points to flowers above the ruins. We listen to Maja’s words about the meaning of the future, in a world staring into the past.

The child understands that it’s the past she must reckon with. She can’t just focus on her own wishes and on the present. The sprawling present that allows the grownup to survey the past as from a distant shore, the same past that blocked their view of everything then.

Haderlap 2011: 81 (translated by Tess Lewis)

We walk towards the rowan trees; they are full with red berries at this time of year. Above the rowans, not far from Auprih farm, where, due to its particular geological composition, the earth has always been more fertile, we stop. We talk about geological periods. From a geological perspective, the Second World War and its horrors are irrelevant. War as one hundredth of a second. “The Karavanke are still growing. The Carinthians feel as if the African tectonic plate will devour them,” explains Zdravko. “Each year it grows by one millimetre to one centimetre.” It is hard to imagine. And yet it is testimony that everything is moving, changing, spinning. Even the ground beneath our feet. There, at the fault between tectonic plates, we talk about the good old days, when each enjoyed a place of their own, where the community took care of elderly, the infirm, the sick, the children, and the eccentrics. Was there really a time like this? A place like this? And what exactly does it mean to have a place of your own? Someone remembers the words of Ursula, the dark-eyed sister of the novel, Storm Still (Ger. Immer noch Sturm), by Peter Handke (Handke 2011), born without a place.

So perhaps it’s true, after all, the other saying from our district, “Only he finds a place who brings it with him”? Did I perhaps never, how can I put it, embody a place? And perhaps that’s exactly why I became the spoilsport for you, worse, the cause of misfortune? It was not you, then, who didn’t leave a place for me, rather that I was already born placeless,.

Handke 2011: 16

We take our snacks at a location of one the scenes of the theatrical play, Angel of Oblivion directed by Zdravko. Over snacks, we talk about women, in fact, the lack of women in the ravines. “Women migrated more than men. They didn’t want to live with their mothers-in-law.” When the Carinthian women migrated, the farms became harsh. We were looking at a landscape of scattered farms that we thought was idyllic a moment before. We see it differently now. We look inside the farms, they’re empty. The trees keep their secrets, the ravines make it impossible to move. Even in reverse. Only the trees insist. “Places of stumbling trees,” wrote Florjan Lipuš in in the novel Boštjanov let [Boštjan’s Flight] (Lipuš 2003).

After a steep climb to a rock from which a modest waterfall flows, we stop. Zdravko heaves Handke’s Storm from his backpack. What Slovenia thinks of Handke is irrelevant here. Hiding under a rock, in the arms of stumbling trees, we read of the “green forces”, of individuals who went into the forests because they had no choice, becoming partisans. Pressed against a wall, as we stand beneath a waterfall, high above our footsteps, reading the words of Handke. Words and footsteps share many things. Gradual progress and perseverance.

Photo: Nataša Rogelja Caf, 2020.

Last stop at the Peršman homestead. We listen to the story of the reconstruction of the monument in St. Ruprecht/Šentrupert near Velikovec/Völkermarkt, which previously stood in front of the museum, a memorial, which was originally dedicated to the fallen partisans at Saualpe/Svinja and blown up in 1953. We talk about installing an accompanying plaque about the homestead at the museum, that was inaugurated in 2012, and about the monument’s design (heroic real socialism with added futurism) and of the inconsistent content, where a forester’s arm, which originally invites resistance, has its hand replaced by a grenade. Due to the thick mass of themes that make it difficult to enter into (any) dialogue, the Kunstraum Lakeside art group decided to undertake an artistic intervention in 2017. The monument is dismantled, relocated to the original St. Ruprecht/Šentrupert site and then returned to Peršman. The intervention is documented. Unspoken dialogue becomes the journey of the monument, its removal and reconstruction, all recorded on film. We listen to Zdravko, we look at the museum, the dis-reassembled monument, the old plaques with the wrong inscriptions, on which new ones have been inscribed. “History cannot be erased,” says Zdravko. We listen to the locals, we sense layers of history, we listen, and then some of us cannot listen further. “I can’t write anymore,” goes into the fieldwork diary. “They buried more than came to the funeral,” continues Zdravko, and though your brains resist what is heard, you automatically sense the words. Maybe there’s a point where the ear canal can no longer take in words. It is not any better in the museum. We watch videos of interviews. We are caught by the voice of one of the survivors, who, in all the events that followed the war, probably thought it would be easier, in that moment, to die under the kitchen table. “I hope my grave is shallow so no one trips over it.” There it is, the kitchen table. His admissions draw memory as a heap and oblivion as a hole. Both cause one to fall.

We take the car down to the valley, accompanied by a verse from Ana Sadovnik’s prose hanging in the museum’s reception area. “Sometimes I’m in the mood to say it, but sometimes I’m not, and no one can get anything out of me. Zdravko drives quickly and confidently. We wind between ravines and houses, the conversation brings us to the present day, an optimistic sounding voice on the radio, then Wake me up when September Ends. September of another age. Stories of the present. War seems far away..

A research walk with a pre-thought out question is a powerful experience similar to anthropological participant observation, but more dense, more intense, perhaps more biased and shallow, but therefore no less seductive. And just as the walking seminar hadn’t started with the first step, but with the reading of the book, it didn’t end with the last. At the end of the walking seminar, each and every one of us, researched in our own way and seasoned his or her research essay – the methodological phase, which was followed by a single walk – with the flavours of each discipline, with shades of each personality, and with experiences of our time. On the phone, each on our end of the line, we re-read Maja’s novel and we stop at the second to last page. “I was brushed by an angel of history,” and we underlined the sentence and headed for the Internet. We search for the father of this angel, Walter Benjamin, who turned his thoughts on the world, time and art into essays.

There is a picture by Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at. His eyes are wide, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned to the past. Where a chain of events unfolds before us, he sees a single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky (Benjamin 2003: 392).

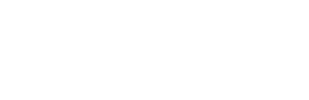

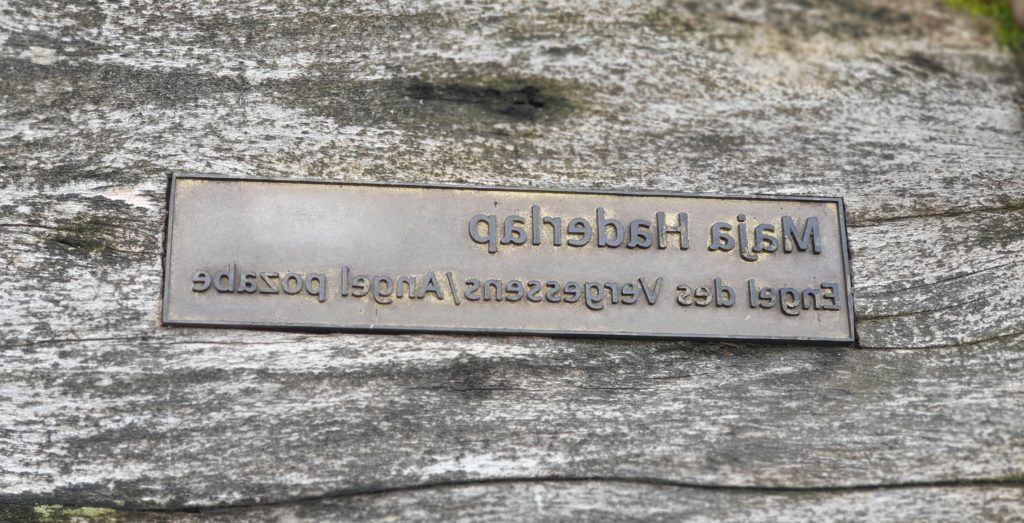

Let us also read the initial research question. “What has been forgotten and what remembered in the Leppen/Lepena valley?” Apart from the analogy of convex and concave – memory as convex piles and oblivion as its concealable opposite, the beginning of the path creeps in our memories. Willi Ošina, on that refreshing September morning gave us a gift, a small wooden panel with an imprint Dr Angela Piskernik / Hoca and Hoti v veliki noči [Hoca and Hoti at Easter]. The reproduction, among many others, was printed from the metal negative stamp attached to the trunk of an old tree resting on the meadow in front of the school. ičon ikilev v itoh ni acoH / kinreksiP alegnA/ retsaE ta itoH dna acoH / kinreksiP alegnA. The mirror-image lettering, oozing from the thick trunk like resin, only becoming meaningful when printed. “It all grows into this tree, the bullet holes, the chain we climbed as children, now we have added these inscriptions,” explained Willi. Angela Piskernik, was the first Slovenian doctorate of science, an ethnographer, a botanist, nature conservationist, active in the Alpine commission, and a spokesperson for the Juliana Alpine Botanical Garden in the Trenta valley, as well as areas of the Triglav Lakes national park. The metal negatives of Angela Piskernik, Florjan Lipuš and Maja Haderlap, trapped in a soft linden tree, act as the collective condensed memory and a reminder. Perhaps that is what remembering and forgetting is all about – transforming or condensing the soft tissue of experience into a solid negative. The negative is neither denial nor oblivion. At first sight, the negative is unintelligible. It does, however, permit memories and reminders to be replicated. At the same time, it conveniently works as a template for the production of souvenirs, in a hands-on kind of way. Although Walter Benjamin was critical of reproduction and reproduction in his essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Ger. Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, 1936) (Benjamin 1998), in our case, reproduction is almost a guarantee of the originality and the authenticity of our memory. Combined with the experience of walking, it allowed us one month later to remember and understand more directly the socio-historical circumstances of the province of Carinthia. And if, in conclusion, we revisit the opening methodological premises of Nick Shepherd, we can agree with his thoughts, that art, in this case, fiction, and other works of art and research interventions such as walking allow a firmer footing, or, as Shepherd says, “more playful”, but no less serious research.

References

- Anderson, J. (2004). Talking whilst walking: A geographical archaeology of knowledge. Area, 36(3), 254–261.

- Benjamin, W. (1998). Izbrani spisi. SH – Zavod za založniško dejavnost.

- Benjamin, W. (2003). Selected Writings. Harvard University Press.

- Baudelaire, C. (1863). Le peintre de la vie moderne. Collections Litteratura.com.

- 2010 = Edensor, T. (2010). Walking in rhythms: Place, regulation, style and the flow of experience. Visual Studies, 25(1), 69–79.

- Haderlap, M. (2011). Angel pozabe. Litera

- Handke, P. (2011). Še vedno vihar. Wieser.

- Ingold, T. (2011). Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Rotledge.

- Ingold, T., Vergunst, J. L. (2008). Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot. Ashgate.

- Ledinek, Š., Rogelja, N. (2000). Potepanja po poteh Šavrinke Marije. Slovensko etnološko društvo.

- Lipuš, F. (2003). Boštjanov let. Litera.

- Pink, S. (2010). Doing Sensory Ethnography. Sage.

- Rogelja, N., Janko Spreizer, A. (2017). Fish on the Move: Fishing Between Discourses and Borders in the Northern Adriatic. Springer.

- Rousseau, J. J. (1796 [1776–1778]). The Reveries of the Solitary Walker. G. G. & J. Robinson.

- Shepherd, N., Ernsten, C., Visser, D. J. (2018). Embodied Research in Emergent Anthropocene Landscapes. In N. Shepherd, C. Ernsten, D. J. Visser (ur.). Walking Seminars: Embodied Research in the Emergent Anthropocene (str. 5). Amsterdam University of the Arts.

- Selwyn, T. (2012). Shifting Borders and Dangerous Liminalities: The Case of Rye Bay. In H. Andrews, L. Roberts. Liminal landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces In-Between (str. 169–184). Routledge.

- Solnit, R. (2014). Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin.

- Thoreau, H. D. (2019 [1862]). Hoja. UMco.

- Woolf, V. (1930). Street Haunting. The Westgate Press.

footnotes

- The contribution was initially published in the Alternator: Think Science in the Slovene language. We are grateful to the editorial board of Alternator for permission to re-publish and to Tamir Azaz for translation.[↑]