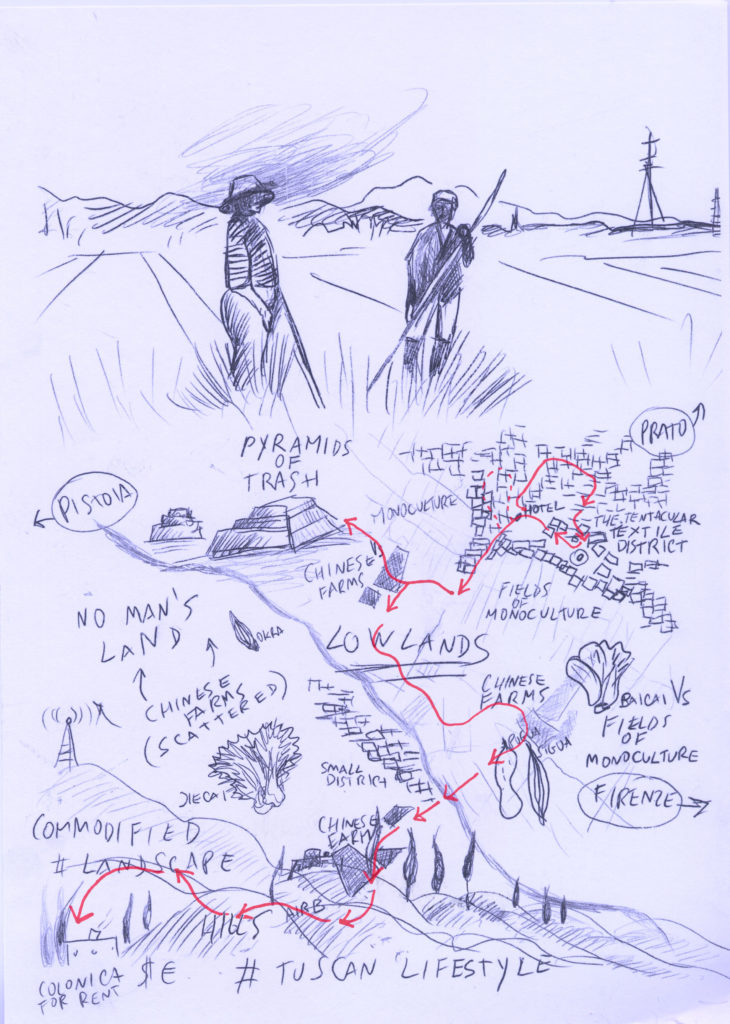

Liminal Landscapes: Notes from a Walking Seminar in the Florence-Prateese Plain

Early May 2023. I’m with a group of researchers from the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. We are taking part in a so-called “walking seminar,”[1] a three-day activity, in which we walk and reflect on migrant legacies in Tuscany. We left the centre of Florence yesterday morning and have now arrived in this remote rural place. What is new to the others is very familiar to me, but I try to see it all through their eyes, as if I were a stranger myself.

From a bird’s-eye view, the area between Florence and Prato is a continuum of industrial buildings interspersed with rural remnants, stretching along the A11 motorway across various municipalities in the provinces of Florence and Prato. The area is a well-known industrial district in Italy,[2] but since the early 1990s it has become world famous as an area with the highest density of Chinese migrants in Europe. Numerous studies on this phenomenon have emerged,[3] and Prato has become a laboratory for researchers from a wide range of backgrounds and disciplines, from sinologists to sociologists and anthropologists to a variety of creative practitioners, working at the intersection of visual arts, theater, photography, or documentary, not to mention activists, journalists, and writers. I consider myself a privileged observer, having lived in the rural areas of Prato for 20 years. Listening, observing and learning from the old and new inhabitants of this place are now part of my everyday life and feed my artistic practice, with which I aim to address the interface between global mobility and rural space. This space is interstitial to but different from the industrial space, and no less relevant.

In front of the dilapidated farmhouse sits a Buddha cast in concrete, surrounded by female-sculptures with undefined classical features. The garden around the house is overgrown while windmills spin tirelessly to recharge exhausted car batteries, apparently for the benefit of no one. Stone-carved dragons and lions lie scattered in the tall grass, while a few dwarf rabbits chase each other and graze the grass, oblivious to our presence. Piles of sand and stacks of unused bricks indicate that some renovation work has been started and suddenly interrupted. Rows of Chinese vegetables, unattended, are thriving in the plots surrounding the farmhouse.

In the early 2000s, this liminal space became a kind of a playground (and battleground) for intercontinental agricultural experiments. Starting with small plots of land behind the Chinese-run textile workshops, Chinese workers gradually leased former agricultural fields that were no longer cultivated by residents and began growing vegetables from seeds they brought from their hometowns in China. This is how the family gardens evolved into farms that were able to meet the needs of the local Chinese community. In 2009, however, hostile media campaigns were unleashed against this rural entrepreneurship, leading to the imposition of heavy fines and often the confiscation of the farms themselves.

The aim of my practice, which takes place at the intersection of art, ethnography and activism (I could simply call it neighbourliness), is not only to retrace the factual chain of events case by case in order to expose the bias of the dominant narrative, but also to examine the ideological intersection of soil, food and the global mobility of humans and plants, where an alien seed can produce unexpected landscapes and trigger a shift in the seemingly solid ground of the landscape that sustains the collective body: the physical, which must be nourished, and the ethical, which must be conceived[4]

Another farmhouse, a few hundred meters further along the riverbank, is undoubtedly abandoned. It appears before us among the branches of the trees as an involuntary memorial to a vanished time, when the numerous mezzadri (sharecropper) families inhabited this now empty corner of the countryside. The uninhabited building stands for an absence at the crossroads of forgotten stories and paths that no one seems to walk anymore.

Many of these houses, called “colonica”, were abandoned during the post-war economic boom, when the farmers – mezzadri – moved to urban areas, lured by the promise of the rapidly expanding textile sector. The 60-year depopulation of the countryside left derelict buildings in its wake; unlike the hilly, panoramic areas of Tuscany, which have undergone extensive renovations and a tourism boom since the 1990s, these farms on the plain have been left to decay.

Nevertheless, the house that stood before us has been revived. About 20 years ago, it was converted into a workshop for fast fashion (pronto moda) by a Chinese entrepreneurial family. Cellars and stables were cleared of oak barrels and troughs and hastily re-paved with modern, easy-to-clean tiles that can bear the weight of sewing machines. People moved back in. After decades of silence, a new language filled the rooms, along with the sound of textile machinery and the smell of home-cooked food that the tenant cooked every day for his employees – and roommates – many of whom were his fellow villagers from the mountainous countryside of southeast China, in the prefecture of Wenzhou. They also planted a small garden in front of the farmhouse to provide fresh vegetables for this transient community. I still vividly remember the first time I saw the green leaves of jiecai (mustard green) radiating light on a gloomy, winter day. I came here after rumors of an unusual and alien renovation, at once scandalous and enticing, had spread quickly through the countryside. In the following years, this garden developed into an actual farm, able to feed the Chinese community working in a very densely populated industrial area.

The criminalization of Chinese manufacturing entrepreneurship highlighted by activists and academics[5]) applies to these rural developments, mirroring (and in a way dramatizing) the demagogic construction of the “parallel district”.[6]) This concept, which has its roots in local media and public discourses, portrays the Chinese manufacturing activities as an alien element that is inherently unregulated and distinct from the official and presumably law-abiding industrial area, a cornerstone of the Italian economy. At the heart of xenophobic narratives about Chinese farmers is perhaps the ideological fear that a foreign, invasive seed sprouting on Tuscan soil (to become food) might somehow threaten the community, both figuratively and literally. As written elsewhere,[7]) the hyper-iconic Tuscan landscape conceals deep ideological deposits that perceive a Chinese vegetable garden as a foreign body and a threat. However, unlike the romantic myths about Tuscany that have been built up since early modernity and reinforced by the rural policies of fascist autarchy and the reuse of a Renaissance iconography by the food, wine, tourism and film industries, the Tuscan landscape has been “a work in progress” for centuries.[8]

This is how people moved back in after decades, had lived here for about 10 years and reactivated a fertile, old soil that had fed generations while they sewed pronto moda. But after a police inspection and the sudden confiscation of property, the house was depopulated again. What we see now are the traces of two worlds that inhabited this place – the Tuscan and the Wenzhounese, like strips of different fabrics woven into a single braid.

After the farm was abandoned, someone used it as an illegal dumping ground, adding to the layers of material remains that now pile together with all kinds of trash, debris and fragmented memories. I find a wedding album from 2017 showing a newly married Chinese couple next to hundred-year-old family photos that have fallen out of some furniture likely dumped here from a nearby town. Plastic mahjong tiles are scattered on the floor, while a rusty, capsized wok slowly sinks into the ground. Broken doors and windows, made by skilled carpenters in a bygone era, slowly rot away. The rain – or other elements – has moved hundreds of buttons and deposited them in the courtyard. They lie together with earth, small debris and shards, like fossils that have settled to the bottom of a geological basin: remnants of fast-fashion, geological sediments of the Anthropocene.

In this broader historical perspective, the seizure of a Chinese farm becomes an uncanny vantage point from which to observe the unfolding of ideological patterns and ask the following questions: How, if at all, are these novel elements inserted into the landscape (and into what people perceive as the “right” landscape)? What if such elements are re-assembled into an anti-landscape, a visual representation of what does not belong? Furthermore, could this emerging landscape[9] defuse the hegemonic iconography of the digitally post-produced Tuscan landscape we all know, by re-cultivating the fertile soil of this rural area, albeit with different seeds? Could a Chinese gourd, along with vineyards, olive trees and cypresses, become part of an imagined, new landscape that reflects an inclusive, sustainable community?

In this place of untamed plants and neglected things, the tidy rows of the family farm have survived the confiscation of the building three years ago: their vivid green marks the only human activity and presence in this part of the lowlands. Through the old plastic sheeting of a tunnel-shaped greenhouse, you can glimpse the lush vines of cucurbits. There, in the artificial biosphere, warm and humid, new life thrives – pugua (bottle gourd), various types of sigua (luffa), kugua (bitter melon), juangua (cucumber) and many others. These summer vegetables will soon find their way to the local Chinese families and restaurants.

We continue along under the riverbank, on the road that runs along the edge of the fields. Two farmers approach us, curious about these unexpected walkers. They lean on their hoes and start a friendly conversation. I see them as guardians of a new biodiversity, custodians of transformative seeds that can sprout into a new world. They share with us fragments of their journey that began in Wencheng near Wenzhou and ended in this rural hinterland of Prato. They talk about the seeds they are sowing. Then we say goodbye. I am grateful for their presence, so charged with personal and political meanings, and I feel a deep commonality with these two unexpected farmers – from the perspective of plants, we are nothing more than vectors, like any other animal that can transport them across geographical boundaries.

Acknowledgments: This essay is part of Semenzaio, a research project supported by the Italian Council (2023).

References

- Becattini, G. (1990). The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion In F. Pyke, G. Becattini and W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Industrial districts and interfirm cooperation in Italy (pp. 37–51). International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Bracci, F. (2012). The ‘Chinese Deviant’: Building the Perfect Enemy in a Local Arena. In E. Bell (Ed.), No Borders: Immigration and the Politics of Fear (pp. 97–116). Éditions de l’Université de Savoie.

- Bressan, M., Krause, E. L. (2020). Viral Encounters: Xenophobia, Solidarity, and Place-based Lessons from Chinese Migrants in Italy. Human Organization 79(4), 259–270.

- Bressan, M., Krause, E. L. (2017). La cultura del controllo. Letture subalterne di un conflitto urbano. Antropologia. Numero speciale.

- Bressan, M., Krause, E. L. (2017). Via Gramsci: Hegemony and Wars of Position in the Streets of Prato. International Gramsci Journal 2 (3).

- Gaggio, D. (2016). The Shaping of Tuscany Landscape and Society between Tradition and Modernity. Ann Arbour: University of Michigan.

- Ceccagno, A. (2012). The Hidden Crisis: The Prato Industrial District and the Once Thriving Chinese Garment Industry. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 28(4), 43–65.

- Ceccagno, A. (2014). The Mobile Emplacement: Chinese Migrants in Italian Industrial Districts, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (7), 1111–1130.

- Greppi, C. (Ed.) (1991). Quadri Ambientali della Toscana – II – Paesaggi delle Colline. Marsilio.

- Giustina, M. (Ed.) (2017). Le inchieste agrarie in età liberale. Polistampa.

- Peretti, J.H. (1998). Nativism and Nature: Rethinking Biological Invasion. Environmental Values 7(2), 183–192.

- Pieroni, A., Vandebroek, I. (2007). Traveling Plants and Cultures. The Ethnobiology and Ethnopharmacy of Migrations. Berghahn.

- Pieroni et al. (2010). ‘My Doctor Doesn’t Understand Why I Use Them’: Herbal and Food Medicines amongst the Bangladeshi Community in West Yorkshire. In P. de Santayana, A. Pieroni, and R. Puri (Eds.), Ethnobotany in the new Europe: People, health and wild plant resources (pp. 112–146). Berghahn.

- Stewart-Steinberg, S. (2016). Grounds for reclamation: fascism and postfascism in the Pontine Marshes. A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 27 (1), 94–142.

footnotes

- The walking seminar was organized in May 2023 as part of the “Heritage on the Margins” research program. Such seminars are semi-curated events in which the (selected) participants (in this case researchers from ZRC SAZU and an artist) reflect on a specific prepared research question, with the participants themselves and the discussions between them being a central source of information for formulating answers to the question posed. One idea behind the walking seminars is the desire to break down the hierarchies between theory and practice, between academic research and creative practice[↑]

- Becattini, Giacomo (1990).[↑]

- Bracci, Fabio (2012), Bressan 2020, Massimo and Elizabeth L. Krause (2017), Ceccagno 2014, Antonella (2012, 2014).[↑]

- The painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti already integrated the civic virtues of the late Middle Ages into the landscape in his work “Effects of Good Government in the Countryside” (1338/39).[↑]

- Ceccagno 2014, A. (2014[↑]

- Bracci, F. (2012[↑]

- Gaggio, D. (2016[↑]

- The “Effects of Good Government in the Country” is the archetype of the modern landscape, that will later play a crucial role in the process of nation-building to intersect with the substance of the national community itself in the form of land and habitat (Lebensraum, spazio vitale), developed along racial lines by totalitarian-fascist ideology and, in other ways, by colonial ideology.[↑]

- Emerging from a not-yet-landscape, consisting of signs not yet codified (if not by its detractors).[↑]